Verona — In Search of Montegue, Capulet, and . . . Crollalanza?

Looking for ‘The Bard’ . . . in Italy?!

William Shakespeare is undisputed as the single greatest playwright and poet to write in the English language. From the sheer craft of the poetic use of language and imagery, to the creation of vivid characters for the stage from paupers to kings and everyone in between, to his ability to reveal simultaneously the complexity and simplicity of the human condition, he is the undisputed best the English language and the English-speaking culture has produced. So, why would a longtime student of Shakespeare such as myself, come looking for him here, in an ancient town in northern Italy half way between Milan and Venice? The easy answer is that two of Shakespeare’s most famous and distinct characters, Romeo and Juliet, lived here in Verona during their short lives on the stage at the Globe Theater around the turn of 17th-century in London. Giulietta, in particular, is an important part of the local mythology of this little town. In fact, we learned that people from all over the world still send letters to Giulietta here in Verona.

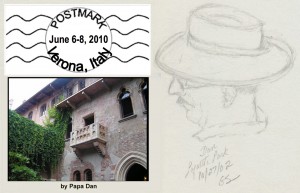

Letters to Giulietta are posted here in the courtyard of 'La Casa de Giulietta' near the Piazza Bra in Verona

How did she and her lover capture the imagination of so many of us?

Romeo Montecchi and Giulia Cappelle were probably real members of two families in Verona who hated each other quite a bit before Shakespeare’s time. A few scholars suggest that Shakespeare may have based his play on a story written by Matteo Bandello around 1550. Whether this story was the source of these actual characters we can only guess; but the Montecchi and Cappeletti families did live here and really did famously feud. Dante, while living in exile in Verona in the early 14th century, actually mentions their names as residents of Purgatorio, presumably as an example of where feuding families end up.

But this speculation does not answer my question, why should we look for Shakespeare himself here in the narrow alleys and ancient piazzas of this little Italian town?

And now for something completely different —

Since the accepted biographical details of the ‘Bard from Stratford’ do not place him anywhere near Verona, a number of questions are unavoidable — Where did this untraveled Englishman get this story? How did he learn so much about Veronese history and culture? Did this man with an undistinguished education write the play at all? Many scholars of this and other plays attributed to Shakespeare suggest other possible playwrights. While I am not going to enter that argument, I am going to start another one — are you ready?

Was Shakespeare Italian?

Over the centuries scholars have been puzzled by Shakespeare’s profound knowledge of things Italian. Shakespeare seemed to have an impressive familiarity with stories by Italian authors such as Giovanni Boccaccio, Matteo Bandello, and Masuccio Salernitano. In an attempt to solve the mystery of Shakespeare’s Italian aptitude, one former teacher of literature has unleashed a new hypothesis on a world eager to hear anything fresh about the Bard.

Retired Sicilian professor Martino Iuvara claims that Shakespeare was, in fact, not English at all, but Italian. His conclusion is drawn from research carried out from 1925 to 1950 by two professors at Palermo University. Iuvara posits that Shakespeare was born not in Stratford in April 1564, as is commonly believed, but actually was born in Messina as Michelangelo Florio Crollalanza. His parents were not John Shakespeare and Mary Arden, but were Giovanni Florio, a doctor, and Guglielma Crollalanza, a Sicilian noblewoman. The family supposedly fled Italy during the Holy Inquisition and moved to London. It was in London that Michelangelo Florio Crollalanza changed his name to its English equivalent. Crollalanza apparently translates literally, from Old Sicilian, as ‘Shakespeare’ (or ‘suddenly shaken or fallen lance’). Iuvara goes on to claim that Shakespeare studied abroad and was educated by Franciscan monks who taught him Latin, Greek, and history. He also claims that while Shakespeare (or young Crollalanza) was traveling through Europe he fell in love with a 16-year-old girl named Giulietta. But sadly, family members opposed the union, and Giulietta committed suicide.

Iuvara’s evidence includes a play written by Michelangelo Florio Crollalanza in the Sicilian dialect. The play’s name is Tanto traffico per Niente, which can be translated into ‘Much Traffic for Nothing‘ or perhaps ‘Much Ado About Nothing.’ He also mentions a book of sayings credited to Michelangelo Florio Crollalanza. Some of the sayings correspond to lines in Hamlet. And, Michelangelo’s father, Giovanni Florio, once owned a home called “Casa Otello”, built by a retired Venetian known as Otello who, in a jealous rage, murdered his wife.

Granted, these similarities between Michelangelo Florio Crollalanza and Shakespeare are intriguing, but for now I remain unconvinced. That Shakespeare was Italian sounds as credible as the idea that Queen Elizabeth I wrote Shakespeare’s works when she was not busy tending to the realm. And I am not alone in my cynicism. While some Shakespearean scholars, most of whom are Italian themselves, are quick to support the hypothesis, the majority are skeptical, to say the least. Although the following excerpt from a biography of Shakespeare by Sir Sidney Lee is not a direct response to Iuvara’s claims, it does illuminate briefly the other side of the argument:

“It is, in fact, unlikely that Shakespeare ever set foot on the Continent of Europe in either a private or a professional capacity. He repeatedly ridicules the craze for foreign travel. To Italy, it is true, and especially to cities of Northern Italy, like Venice, Padua, Verona, Mantua, and Milan, he makes frequent and familiar reference, and he supplied many a realistic portrayal of Italian life and sentiment. But his Italian scenes lack the intimate detail which would attest a first-hand experience of the country. The presence of barges on the waterways of northern Italy was common enough partially to justify the voyage of Valentine by ‘ship’ from Verona to Milan (‘Two Gent.’ I.i.71). But Prospero’s embarkation in ‘The Tempest’ on an ocean ship at the gates of Milan (I.ii.129-144) renders it difficult to assume that the dramatist gathered his Italian knowledge from personal observation. He doubtless owed all to the verbal reports of traveled friends or to books, the contents of which he had a rare power of assimilating and vitalizing.” (Lee 86)

“It was not unusual for an Elizabethan dramatist to set his or her play in Italy. Are we, knowing this, compelled to assume that Marlowe, Bacon, and Jonson were Italian?”

“Admittedly, we do not have much information about Shakespeare’s education, but why is it easier for Iuvara to assume that Shakespeare was an Italian refugee than it is to assume that he mastered Italian culture and history on his own? Jonson’s verses in the Folio identify Shakespeare as the ‘Sweet Swan of Avon’, and his birth record and other important documents attest to the fact that Shakespeare was a resident of England his whole life. Yet some choose to ignore these pieces of evidence in favor of more esoteric theories. One thing is certain – Iuvara’s claim that Shakespeare was Italian will unite Shakespeare supporters and anti-Stratfordians from the camps of Bacon, Essex, Marlowe, Derby, Rutland, Oxford, and Queen Elizabeth in a mutual uproar.”

Further Reading

Lee, Sir Sidney. A Life of William Shakespeare. New York: Dover Publications, 1968.

Based on : Was Shakespeare Italian? Shakespeare Online. 20 Aug. 2000. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/biography/shakespeareitalian

===================

OK, so there you have it — a perfectly ridiculous idea that is the direct result of spending a few days in Verona. It can have that effect on a person. After a few terrific dinners and bottles of local wine in the little restaurants tucked away in the alleys of Verona (two of the best restaurant experiences we’ve had in Italy) and it’s not so difficult to imagine all sorts of stories that put this little town firmly in the center of the universe.

So, why do so many Shakespearean scholars in Britain go to so much effort to refute such an outlandish idea? To use some of the Bard’s own words, “Methinks they dost protest too much.”