Archive for Baseball

Baseball Rules — 2019

To those who think baseball is dull

and want to speed up the game:

“Tell them two things:

First, explain the planning, strategizing,

calculating, and deception

that takes place before every pitch.

Then, quote Hall-of-Fame announcer Red Barber

— ‘Baseball is dull only to dull minds.’ ”

Click here to download a PDF of this post:ConVivio_baseball_rules_Mar2019

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Baseball It’s the middle of March, and right now I am deeply embroiled in Golden State Warriors’ basketball. The NBA playoffs are fast approaching and there is much at stake. Heck, there’s an important game tonight (aren’t they all?). BUT the sun is shining this week and baseball is in the air. So, there are some things we must discuss.

It’s the middle of March, and right now I am deeply embroiled in Golden State Warriors’ basketball. The NBA playoffs are fast approaching and there is much at stake. Heck, there’s an important game tonight (aren’t they all?). BUT the sun is shining this week and baseball is in the air. So, there are some things we must discuss.

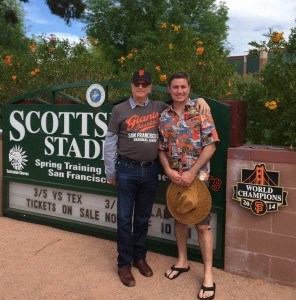

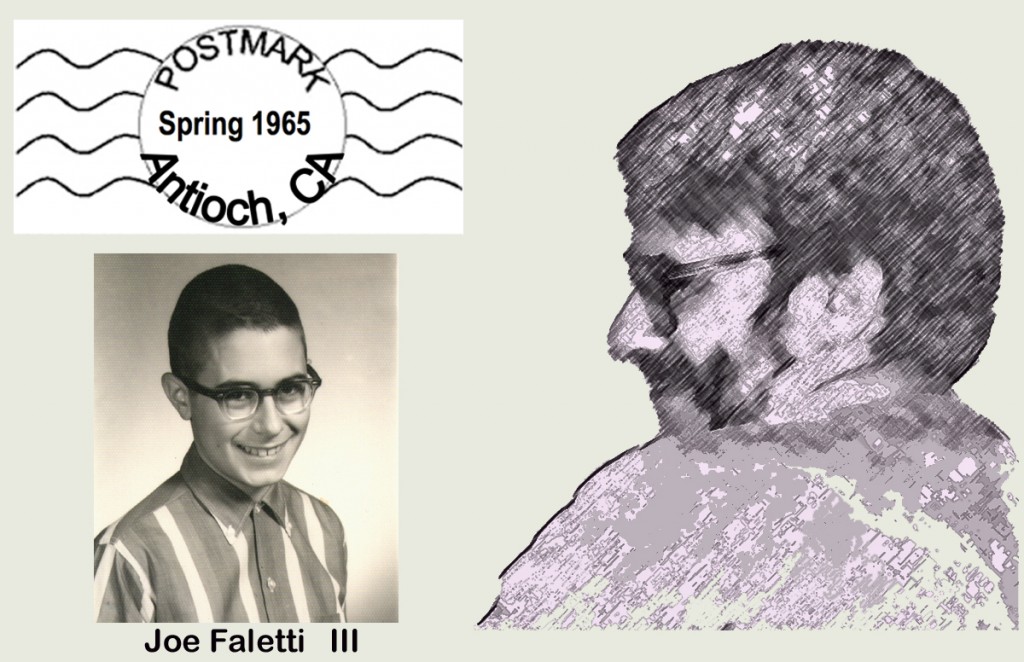

Disclaimer: As I’ve written before, I was a basketball player, not much of a baseball player. Basketball was the only sport I was any good at, but I grew up loving baseball — I watched it ever since 1961 when my brother-in-law Joe Faletti took me and my nephews to my first Giants’ game at Candlestick Park. I listened to Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons on the radio and I lived and died by the fortunes of My Giants. Baseball mattered to a kid growing up in the 1950s/60s in Antioch, CA. [Click here for my personal, brief playground baseball history.].

While I was not a baseball player in the 1960s, I read everything I could get my hands on about baseball heroes ancient and current and came to understand that much about baseball had not changed in a very long time and that was the way it was s‘posed to be. THAT meant that the achievements of ancient players I read about — Babe Ruth, Bobby Thompson — were just as important as, and comparable to, those of the heroes of my youth— Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, and the rest of My Giants — and those of today’s 21st-century Giants — Buster Posey, Madison Bumgardner. It also meant that the strategies of baseball managers — from Leo Durocher to Alvin Dark to Bruce Bochy — didn’t change either.

Of course, I learned early that in baseball, as with any sport, the rules mattered. I needed to know the rules inside and out if I hoped to have intelligent conversations about baseball with other kids and adults — or if I was going to follow what I was hearing on the radio.

Last year at this time, I wrote about My Giants and it was mostly paying homage to baseball memories (click here to take a look at that one: Baseball 2018).

So, what is this Giants fan thinking about, here in March of 2019?

Baseball Rules

Baseball has two kinds of rules: unwritten rules and written rules.

The Unwritten Rules of Baseball

The unwritten rules of baseball must NEVER be violated. There are 29 of them. I will offer these six to serve as examples:

Unwritten baseball rule #2: Thou shall not say the words “No hitter” in the midst of a no hitter. The penalty for violating this rule is that a no hitter will not happen.

Unwritten baseball rule #5. Do not make the first or third out in an inning at third base. You’re already in scoring position at second; don’t be greedy.

Unwritten baseball rule #11. Do not “show up” the other team or a player. This means don’t admire a home run you have hit or gesture happily after striking someone out. Act like you’ve done it before and you expected it. Otherwise, bad things will happen.

Unwritten baseball rule #18. Stealing signs is allowed, if you don’t get caught. BUT, do not peek at the catcher’s signs while you are hitting. If you do, the next pitch will be aimed at your head.

Unwritten baseball rule #23. A pitcher that is getting pulled from the game must always HAND the ball to the manager while he waits for him ON the mound. This rule has been violated occasionally by players who had short careers in the major leagues.

Unwritten baseball rule #27. Do not step on the chalk lines as you walk on or off the field. Bad things will happen if you do.

These “rules” have been in force for the better part of 150 years and do not change. Period.

The Written Rules of Baseball

OK, now we get to the REAL issues that loom over major league baseball today. As reported recently in the NYT and the SF Chron, a number of dramatic rule changes have been swirling around Major League Baseball (I tried to avoid adding the phrase ‘like a plague of locusts’). To most of us who grew up with baseball as an everlasting, never-changing presence in our lives, these suggestions have been dismissed as meaningless meanderings of deranged minds. BUT, these are starting to get serious — SO SERIOUS in fact, that the independent minor league Atlantic League will be testing some of the proposed rules this coming season. This ‘very minor’ league has eight teams spread across the country from New York to Texas. Below is a quick summary of some of the new rules they will be trying out and a humble assessment of them.

Three-batter minimum: Once a relief pitcher enters a game, he must face at least three batters, unless the half-inning comes to an end. If you’re the manager under this rule, you won’t be allowed to bring in a particular pitcher to pitch to one particular hitter and then pull him out.

— According to Bruce Jenkins, MLB is considering implementing this rule in 2020, even if the players union protests.

— In My Humble Opinion (IMHO): this is crazy.

Extra-inning “tiebreaker”: To prevent really long extra-inning games, each extra half-inning would begin with a runner on second base. According to Bruce Jenkins: “… no chance.”

— IMHO: This is pure evil. I still remember listening to my transistor radio lying in bed late into the night of July 2, 1963. Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves and Juan Marichal of the SF Giants BOTH pitched 16 shutout innings tied 0-0 until Willie Mays came up in the bottom of the 16th and hit one into the left field stands to win 1-0. Historic games like this should not be made unlikely with silly rules like this one.

Banning the shift: This rule would require that two infielders be stationed on each side of the second-base bag when the pitch is released — otherwise, a ball is called.

— Once again, it takes a strategic option away from a manager and it deprives us all of the possibility of seeing a powerful pull hitter try to lay down a surprise bunt (in my memory McCovey tried this at least once). MLB plans to consider this one for the 2020 season.

— IMHO: NO! Managers should be able to position their defense anywhere they think would be to their advantage. If they try something unusual and get burned — that will be entertaining.

Mound visits eliminated: That’s right, no visits by a catcher, infielder or manager unless a pitching change happens.

— MLB reduced the number of visits and may drop it to four for 2020. Some want visits ended.

— IMHO: There are good tactical reasons for having strategic discussions in key situations, even to stall for time while a pitcher warms up in the bullpen. I say don’t limit visits any further. Adding some thought and discussion to the game is a good thing — and what’s your hurry?

“No Pitch” intentional walks: What about the idea of intentionally walking a batter by simply waving him to first base? Over the years there have been times when a runner advanced because an intentional ball got away from the catcher — in some cases a runner has scored from third.

— IMHO: I don’t think it is an improvement to remove an opportunity for players to make a mistake with consequences. That’s a key part of the game. I say make them throw the pitches.

Pitch clocks: For years, the Official Baseball Rules requires that the pitcher shall deliver the ball to the batter within 12 seconds after he receives it, if the batter is in the box. MLB could simply enforce the existing rule, but the players hate it.

— IMHO: as my Italian ancestors used to say “Fuhgeddabowdit.”

Reduced time between innings: The Atlantic League will be cutting commercial time from 2:05 to 1:45. MLB is reducing the time from 2:20 to 2:00 in national telecasts.

— IMHO: I don’t care about this one, since there are easy technical work-rounds for television.

The mound moved back: The mound has been 60 feet, six inches from home plate since 1893

— the Atlantic League is going to move it back two feet to 62 feet, six inches. The idea is to cut down on the increasing number of strikeouts — a good thing — which it is likely to do.

— IMHO: this is outrageous and the second-worst rule-change idea I have heard. This would change everything and make all of our historic standards and records meaningless. Fortunately, MLB doesn’t seem to be interested in it — but it’s early. You should worry.

Robot umpires: This one is the single worst rule-change idea I have heard. While proposals for implementation of this plan are not as horrific as the name suggests, in this plan, balls and strikes will be called digitally and relayed to a human umpire; but fortunately, MLB does not appear to be seriously interested.

— IMHO: Absolutely NOT! If there’s one idea that has always — rightfully — dominated the game of baseball it is that it is a human endeavor built entirely on the reality that outcomes on the field will be determined by the imperfection of the participants at a particular moment. Routine plays will happen as they should; great plays will be noted as grand surprises; and mistakes will be something we must live with. I believe this ”rule” must always also apply to the performance of umpires. If the decision made on the field is an error, we should be stuck with it, just as we are stuck with it when an outfielder throws to the wrong base or a base runner misses a bag.

So, What’s The Hurry?

So, in summary, I will continue to be skeptical of any proposed rule change that is intended to “speed up the game.” All my life, baseball has been called “Our National Pastime.” That name implies that it should be a pleasant way to PASS the time, not to rush through it or shorten it. Sitting in the stands at the ballpark on an afternoon or evening was always intended to be a leisurely time, a time to allow the mind to wander a bit.

And so, IMHO, that is the way it must remain.

![]()

Baseball 2018

There are only two seasons:

Winter and Baseball.”

— Bil Veeck

“Baseball is ninety percent mental

and the other half is physical”

— Yogi Berra

Click here to download a PDF of this post: ConVivio_baseball_Feb2018_Final

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Baseball

Here in February, the day Lou Seal shows up at my granddaughter’s school in San Francisco, in full uniform, you KNOW baseball is just around the corner. Why did he appear at Quinn’s school? Was it to introduce young people to the magic of baseball and the optimism that spring training embodies? The timing is clear: Spring Training is about to begin and, once again, it’s magic. All you have to do is say the words “Spring Training” and serious baseball fans can feel the magic.

Here in February, the day Lou Seal shows up at my granddaughter’s school in San Francisco, in full uniform, you KNOW baseball is just around the corner. Why did he appear at Quinn’s school? Was it to introduce young people to the magic of baseball and the optimism that spring training embodies? The timing is clear: Spring Training is about to begin and, once again, it’s magic. All you have to do is say the words “Spring Training” and serious baseball fans can feel the magic.

Disclaimer: I was a basketball player. It was the only sport I was any good at, but I grew up loving baseball — I watched it ever since 1961 when my brother-in-law Joe Faletti took me and my nephews to my first Giants’ game at Candlestick Park; I listened to Russ Hodges and Lon Simmons describe it on the radio; I lived and died by the fortunes of My Giants. Baseball mattered to a kid growing up in the 1950s/60s in Antioch, CA. It became personal. [Click here for my personal, brief baseball history.]

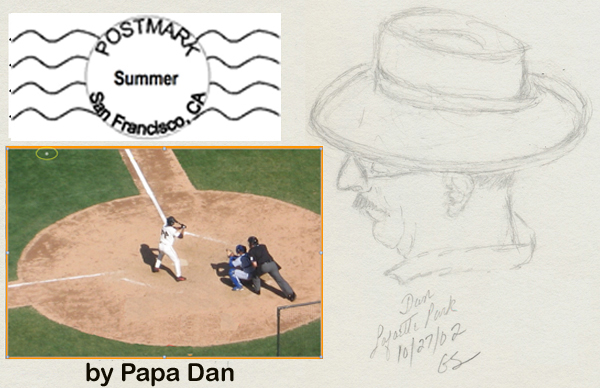

In baseball, the approach of Spring Training is a hopeful time — no scores yet, no losses, no strikeouts or disappointments. Even after My Giants’ dreadful 2017 season (we’re not gonna talk about that) the slate is clean and all things are possible. In 2016, my son Matt and his wife Nou took Gretta and me to our first Spring Training in Arizona. It was a sweet gift. [Click here for that story] Now I grant you, today I am deeply involved in the Warriors’ effort to win another NBA championship. That’s a very big deal. But baseball is something more.

So, what is this Giants fan thinking about here in February, 2018?

To get us ready, let’s listen to some (mostly) REAL baseball people who have gone before us:

- George Will: “Baseball, it is said, is only a game. True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona. Not all holes, or games, are created equal.”

- Terrence Mann (James Earl Jones from “Field of Dreams”): “And they’ll walk out to the bleachers; sit in shirtsleeves on a perfect afternoon. They’ll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the baselines, where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they’ll watch the game and it’ll be as if they dipped themselves in magic waters. The memories will be so thick they’ll have to brush them away from their faces. “

- Dr. Archibald “Moonlight” Graham: “Well, you know I … I never got to bat in the major leagues. I would have liked to have had that chance. Just once. To stare down a big-league pitcher. To stare him down, and just as he goes into his windup, wink. Make him think you know something he doesn’t. That’s what I wish for. Chance to squint at a sky so blue that it hurts your eyes just to look at it. To feel the tingling in your arm as you connect with the ball. To run the bases – stretch a double into a triple, and flop face-first into third, wrap your arms around the bag. That’s my wish.”

- Ted Williams: “Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of ten and be considered a good performer.”

- Gerald R. Ford: “I watch a lot of baseball on the radio.”

- Jim Bouton: “You spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball and, in the end, it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

It’s About Memories

It turns out that a lifetime of baseball is a lifetime of memories. If you’I bet you have plenty of your own. As a kid standing in the right field bleachers at Candlestick Park during batting practice, I remember when Willie Stargel of the visiting Pittsburg Pirates hit a ball over the right field fence into a gaggle of kids hoping to snatch the ball. After the ball bounced off the concrete, I remember seeing a hand reach up out of the bunch and grab the ball. What a surprise to learn that hand belonged to my nephew Steve Faletti, who walked away with the baseball. For me that same day, what kind of thrill was it to stand behind the centerfield fence about twenty feet from the greatest player of all time: Willie Mays?

So many memories followed that one.

On the evening of July 2nd, 1963, I finished my homework listening to a pitching duel between Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves and Juan Marichal of My Giants on the “leather radio” my dad had given me. By the time I needed to go to bed the score was 0-0 starting the ninth inning.

I couldn’t turn it off with that score, so I snuck my transistor radio under the pillow and decided to hear the end of the game in bed. Twenty-five-year-old Juan Marichal came out and continued his shutout in the tenth and, to some surprise, forty-two-year-old Warren Spahn did the same. Turned out that the dual shutout continued until, with my transistor radio still in my ear, Willie Mays hit a walk-off home run into the late-night darkness in the bottom of the 16th inning. The next morning the SF Chronicle quoted a dejected Spahn as saying, “I threw him a screwball and it just hung there, it didn’t do a damn thing.” When asked if he was surprised that is manager kept him in the game so long, Spahn growled “If that kid can pitch 16 innings, I sure as hell can.”

OK, fast forward 54 years to May 12th, 2017 — 25-year-old Giant catcher Buster Posey comes up to bat, this time at AT&T Park, in the bottom of the 17th inning against the Reds. Same story — Buster hit a similar walk-off home run over a different left-field fence. Willie (age 86) and Buster (25) got to talk about it (below). [Read the story.] On this night, however, nobody pitched a complete game — alas, such is the nature of the game here in the 21stcentury.

The Nuschler

Another Giant favorite, Will Clark, was known as “Will the Thrill” from his days playing high-school ball in Louisiana. He lived up to that name in his first major-league at-bat hitting a home run off Hall-of-Famer Nolan Ryan in 1986. He went on to hit 35 homers in 1987, leading his (and My) Giants to the playoffs for the first time since 1971. But my enduring memory came at the end of the 1989 NL playoffs when he hit the ball up the middle to drive in the game-winning runs sending them (us) to the World Series. But, that series turned out, well … we’re not gonna talk about that.

But I digress. Where was I? Oh, yes …

“The Nuschler” (from his actual middle name) is the name given to Clark’s “Game Face” during his rookie year with the Giants, a face described by a teammate as a combination of confidence, satisfaction, arrogance, and just plain oblivion.”

Giant Plans to Make New Memories in 2018

A whole bunch for things need to go right for my team to be a playoff contender this season. Let’s face it, last year (64-98) is a tough experience to build on (we’re not gonna talk about that). But, in the spirit of the ‘new beginning’ that Spring Training always promises, there is hope.

Thing One — Pitching: Madison Bumgarner. He needs to pitch well enough to be in the running for the Cy Young Award. He needs to start 30 games and My Giants need to win more than 20 of those to be contenders. Period. Johnny Cueto and Jeff Samardzija can certainly be expected to improve as are Chris Stratton and Ty Blach to round out the starting staff with Tyler Beede and Andrew Suarez lurking in the wings. (There has been recent talk about a return of Tim Lincecum, but that’s still just talk.) So, no question the pitching staff must step up and there’s no reason to doubt that possibility. It’s Spring Training, right?)

Thing Two — Offense: IF Bumgarner and the rest of the pitching staff come through as we hope, we’re going to need to score more runs than last year, right? I’m looking for Jarrett Parker to step forward and improve on his .247 average and 23 RBIs. He can do better than that. We know that Hunter Pence is capable of improving on his 2017 numbers (.260, 67 RBI) as is “The Panda” (.220, 32 RBI). The Brandons can be expected to top last year’s stats (Crawford: .250, 77 RBI, 14 HR; Belt: .241, 15 RBI, 18 HR). Joe Panik can at least repeat his numbers (.288, 53 RBI, 10 HR). No need to worry about Buster Posey — we can count on at least his .320, 67 RBI, 12 HR numbers from 2017; and his handling of the pitching staff will, of course, be crucial.

Trade rumors are still circling, but as of Monday morning, rumors about Panik, Chris Shaw, and Tyler Beede seem to be quashed. So, it looks like Panik (and his bat) will be starting at second base for the Giants. According to the Chron, he is (and we are) happy about that.

The Giants signed two former Pirates — Outfielder Andrew McCutcheon and LH pitcher Tony Watson — among several players added this month. They also announced 28 non-roster invitees to Training Camp and, as in the past, some pleasant surprises may emerge from that list.

Thing Three — Groan-Ups Meddling with the Rules: Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred announced on Monday that new rules are in place to speed up the pace of MLB games this season. The plan is to limit trips to the mound (six per game by coaches and players), reduce the time allotted for pitching changes, and shorten the breaks between innings (by five seconds). You won’t believe the specific times and circumstances listed in the new rules (and, believe me, you don’t want to know). But, resisting this rising tide of time-slicing, the players union rejected the idea of a 20-second pitch clock. Whew.

And what problem are they trying to solve? Last year’s games averaged 4½ minutes longer than 2016. Here is my editorial comment à à à I think this effort to speed up the game is … well … bull-babble (did I make up a new word?). The game was intended to be slow-paced and thoughtful. These rule changes and the attempt to gain back that 4 ½ minutes are ridiculous.

So, there!

Thing Four — What Does Vegas Say?: Odds makers have established an early favorite to win the 2018 World Series. Before I tell you their prognostication, let me tell you an important part of my upbringing. You may be surprised to hear that I grew up having two favorite baseball teams:

1. The San Francisco Giants

2. Any team that happens to be playing against the LA Dodgers on any particular day.

With that in mind, who does Las Vegas predict will win the World Series in 2018?

We’re not gonna talk about that!

P.S. And, of course, this one — technically in my lifetime — is still my favorite memory:

Watch Bobby Thompson’s

“Shot heard round the world,” in 1951

The New York Giants beating the Brooklyn Dodgers

to advance to the World Series.

(Yes, the voice is Russ Hodges)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lrI7dVj90zs

And one final quote, from Yogi Berra: “It’s fun; baseball’s fun.”

We could all use more of that fun, d’ya think?![]()

Talkin’ Baseball … Math

“Using wrong measurements has

“Using wrong measurements has

resulted in bad decisions on contracts,

playing time, trades, and draft picks.”

“It’s led to picking the wrong players

for MVP, Cy Young, and Rookie of the Year

and even obvious stuff like the Hall of Fame.”

“It drives conversations about teams

and players right off the cliff.”

— Keith Law,

from his new book “Smart Baseball”

…

Click here to download a PDF of this article: ConVivio_Baseball_math

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Getting Baseball Wrong: By the Numbers

Baseball writer Keith Law has written an unusual book about the way we evaluate baseball players and teams — something we’ve all been doing since we were kids. He makes a case that we’ve been getting it wrong throughout the history of baseball. Let’s consider his observations.

When I saw his book, “Smart Baseball,” on the library’s ‘New Books’ shelf, I thought it was about something else — you know, how to PLAY baseball smarter. I thought it might be useful for talking about baseball with my grandchildren. But it’s about something else that all fans do: comparing players and teams during the season and, a tougher task, comparing today’s players and teams with those of the past. We use statistics; and it affects a lot of baseball judgments.

First, how DO we evaluate and compare hitters?

Most of us have known these rules since we were kids.

1. We evaluate hitters by their batting averages, runs batted in, and slugging percentage.

• Batting average (BA): the number of base hits divided by the number of official times at bat — example: a batter who gets 30 base hits in 100 at-bats has a batting average of .300. In this calculation, all hits are treated as equal.

• Runs batted in (RBIs): the number of times a batter causes a runner to score because he gets a base hit or walks in a run — examples: a batter who gets a base hit driving in runners on second and third is credited with two RBIs; a batter who walks with the bases loaded is credited with one RBI. (BTW, a batter who hits a ball “booted” by a fielder causing a run to a score on the error does NOT receive an RBI.)

• Slugging percentage (SLG): the total bases a batter reaches divided by the number of official at-bats. Regardless of the number runs that are produced, a double is counted as two total bases; a homer is four. So, this statistic claims to measure the extent to which a hitter is a “power hitter.” A batter who has 100 official at-bats and hits 20 singles, eight doubles, and two homers has a slugging percentage of .440.

These numbers have been used for making decisions on trading or acquiring players (or baseball cards), selecting a Most Valuable Player (or other batting awards), and setting salaries, literally for centuries. So, how well does that work?

Let’s See

Every year the major leagues give their “Batting Champion” award to the player with the highest batting average. The assumption is that this is the single statistic that identifies the best hitter. In 2015, the Miami Dolphins’ Dee Gordon led the National League with a batting average of .333. So, he was the 2015 NL Batting Champion. That was easy.

–> –> BUT, Bryce Harper of the Washington Nationals led the league in almost everything else that year: doubles, homers (42 to Gordon’s 4), walks (124 to Gordon’s 25), and runs scored. Harper beat Gordon in RBIs (99 to 46) and Slugging Percentage (.649 to .418). So, who was the best hitter? If the offensive goal of a baseball team is scoring runs to win games, which of them would you want on your team? Oh, by the way, Harper was also the National League’s MVP, but, Gordon was the NL Batting Champion. So, tell me — what did that mean exactly?

What about RBIs?

Maybe the number of runs that score when a batter gets base hits is a better gauge of a hitter’s ability. This statistic has long been valued in voting for MVP candidates, as it was (above) in 2015 in the National League. Despite the important role of the RBI stat in baseball reporting, many writers point out that it is one of the individual stats that depends almost entirely on the achievements of other players — specifically, how many players are on base when a batter gets a hit. Examples abound, but comparing two famous careers serves at least to consider the importance of the RBI statistic:

• As we all remember (with varying degrees of admiration for off-the-field reasons), Barry Bonds was the major leagues’ all-time career leader in home runs with 762 compared with Henry Aaron’s 755. To fill out the picture, judging them ONLY by their actual offensive statistics, Bonds hit those home runs in 300 few games than Aaron, got on base more often (.444 to .374), and hit for more power (i.e., a higher slugging percentage .607 to .555), was walked almost twice as many times (2558 to 1402), and was the National League MVP seven times to Aaron’s one. SO, what about RBIs? With all those numbers what would you guess?

Aaron had 301 more career RBIs than Bonds. Why? During his most productive seasons, Bonds batted third in a Giants’ lineup in which two of the three players who batted ahead of him were not so good at getting on base. This fact is what Keith Law refers to as one of the “stupid manager tricks” that make RBIs such a weak indicator of a hitter’s ability. Turns out that Bonds has the distinction of hitting 450 solo home runs in his career. So, Bonds’ lower RBI total has more to do with the lineup that batted ahead of him than anything about his own hitting prowess. So, what does a player’s RBI total tell us about a player’s hitting ability?

Not so much.

What about pitchers?

We evaluate pitchers by the number of “Wins,” Saves,” and Earned-Run Average (ERA). How does that work out? All our lives, starting pitchers have been labeled by the number of “Wins” they are credited with. There are other pitching stats, but they all take a back seat to the “Won-Loss” record. We all want our pitching rotation to include “20-game-winners.” This statistic is simply dumb. While team victories matter more than any other team statistic across a 162-game season, author Keith Law asserts “the idea of a single player earning full credit for a win or blame for a loss exposes deep ignorance of how the game actually plays out on the field.”

I grew up in an era when a manager hoped, and a pitcher intended, that he would pitch a “complete game.” Today — nope. Today, managers typically keep a starter on the mound for 100 pitches, certainly not more than 120. Example: in April of 2016, Dodgers’ rookie Ross Stripling was pitching a no-hit, perfect game in the 8th inning against the Giants when, after his 100th pitch, he was yanked for a reliever. The Giants wound up winning 3-2 on Brandon Crawford’s 10th-inning homer. Contrast that with a game I listened to on my transistor radio back in July of 1963 when 25-year-old Juan Marichal battled 42-year-old Warren Spahn on the mound into the 16th inning, both pitching a shutout, when Willie Mays broke up the party with a 16th-inning homer to win for the Giants 1-0. Even though Spahn had to pitch himself out of a bases-loaded situation in the 14th inning, both managers did the obvious thing — left their best pitcher in the game when they were pitching a shutout in a game they wanted to win. SO, what does it mean? In the first example, Ross Stripling pitched 7+ innings of perfect baseball and it didn’t even show up in his Won-Loss record. In the second example, Warren Spahn finished the season with a 23-7 Won-Loss record; and this game, arguably one of the best pitching performances in history, was just one of his seven losses. What did that statistic mean?

Not much.

Conversely, a “Win” doesn’t always mean that pitcher even pitched well. Example: in the 2000 season, Russ Ortiz pitched 6 2/3 innings and gave up ten runs; but he got the win because his team scored 16 runs that day. Truth is, a “Win” or a “Loss,” as a pitching statistic, depends on the work of many other players — sometimes not because of, but IN SPITE OF the pitching performance. Then, when you factor in the role of relief pitchers who preserve a “Win” for a starter and the very real contributions of the defense and offense of a pitcher’s team, the “Win-Loss” record is pretty useless in evaluating a pitcher’s ability. AND that doesn’t even consider the number of good pitchers who played long careers for bad teams.

So, let’s agree that the “Won-Loss” record is, at best, misleading.

So, what about “Saves?” Rule 10.20 determines that a relief pitcher earns a save when he:

• finishes a game his team wins and he is not the winning pitcher; and any one of these apply:

— enters the game with a lead of no more than three runs and pitches at least one inning

— enters the game with the potential tying run on base or at bat or on deck

— pitches effectively for three innings.

If he meets these criteria, he earns a “Save” — whether he pitches well or poorly; OR he can pitch very well and NOT earn a Save under the wrong conditions. Keith Law tells us: in 2015, there were 114 appearances when a relief pitcher pitched at least three innings and gave up zero runs; but only NINE of those appearances earned the pitcher a “Save.” Compare that to the thirteen saves that year earned by pitchers who allowed two runs in one inning of work, but protected a lead and finished the game. Pitch four scoreless innings in a loss — no save. Give up two runs in the last inning — save. SO, what does the “Save” statistic mean? It’s all about factors that have little to do with the performance of the pitcher. BUT, for relief pitchers, it’s a key contributor to salaries, trades, and recognition.

What about “Earned Run Average (ERA)?”

This stat is a staple on baseball cards and on-screen graphics along with the Win-Loss record. It is the number of earned runs allowed per nine innings pitched. Earned runs are, of course, those that result from base hits and not caused by errors or passed balls. But, it does not account for the ability of outfielders to hold a hitter to a single, throw out runners on the bases, or the subjective work of official scorers to distinguish hits from errors. So, aside from strikeouts and walks, the act of getting a batter out or preventing runs from scoring is shared by others.

While ERA has limited value for evaluating starting pitchers, it is even more misleading for relievers. When a starting pitcher gives up a single, a double, and an intentional walk, he is responsible for those runners. When the relief pitcher replaces him in the 7th inning with the bases loaded and gives up two more singles before retiring the side, all three of the resulting runs are charged to the starting pitcher, none to the reliever. While getting outs is the primary task of any pitcher, it is too easy for a relief pitcher to come in during a tough situation, pitch badly, and leave with his ERA intact. The resulting stat is not an accurate reflection of who did what or the effect their performances had on the outcome of the game. We could cite many examples of the assignment of earned runs in a variety of situations and none would be entirely satisfying. In general, ERA is another case of baseball math that depends more on the sequence of events and the contribution of others than the quality of individual performances.

So, what’s better?

In recent years, something called “Sabermetrics” has begun to creep into the mainstream of baseball writing and even management decision-making (remember the movie “Moneyball?”). Serious statisticians are now employed by more MLB teams every year and they are looking at some different numbers. The book “Smart Baseball” asserts that “On-Base Percentage (OBP) is the most complete of all basic hitting stats, because it includes everything a hitter does” and it excludes many factors that are not specific to the hitter’s individual performance.

OBP = (Hits + walks + times hit by pitch

divided by

(At bats + walks + times hit by pitch + sacrifice flies)

The logic is simple: take the number of times a hitter gets on base and divide it by the total number of times he came up to the plate. Using the 2015 season of Bryce Harper (mentioned above) as an example, this method would have given him an OBP of .460 (46%). If that statistic had been used in 2015, Harper would have easily been the Batting Champion instead of Dee Gordon who simply had a higher batting average by .003.

Again, statistical examples are numerous — let’s return to our previous example:

In 1987, the National League MVP was Andre Dawson. Dawson hit 49 home runs for the Cubs along with a batting average of .287 and 137 RBIs, and a slugging percentage of .568. OK.

However, Keith Law asserts that the real MVP that year should easily have been Tony Gwynn. While Dawson had more home runs and RBIs, Gwynn dramatically overshadowed Dawson in singles, doubles, triples, walks and — here’s the key: he had an On-Base-Percentage (OBP) of .447 compared to Dawson’s .328. Another way to look at it, given that they had a nearly identical number of plate appearances, Dawson made 70 more outs than Gwynn that season. SO, by their own individual contributions, which of them increased their team’s ability to score more runs? If that is the most important objective, it seems that our traditional baseball math may have chosen the wrong MVP in 1987. Using OBP could have suggested another choice.

One small refinement has emerged — the “triple slash” stat: batting average/on-base percentage/slugging percentage. In that case, here is the snapshot of those 1987 performances.

BA OBP SLG

Dawson: .287/.328/.568

Gwynn: .370/.447 /.511

What’s the effect on the recognition of pitchers?

The most prestigious single-season recognition for pitchers is the Cy Young award. As a quiz, let’s take a look at the details of the Cy Young decision in a year you might not remember, 1990, and see if we can decipher how that decision was made. Here were the top candidates:

W L ERA IP Runs

Bob Welch (Oak): 27 6 2.95 238 90 (78 earned)

Dave Stewart (Oak): 22 11 2.56 267 84 (76 earned)

Roger Clemens (Bos) 21 6 1.93 228 59 (49 earned)

Do you remember who won the award? Without looking, who would get your vote? (Hint question: does one statistic dominate Cy Young award voting?)

Bob Welch won the award. Why? Of the three contenders, Welch gave up more runs, had the worst ERA, and . . . well, he had the best Won-Loss record — the one stat that depends the most on the work of others. Was he the best pitcher that year? Heck, Keith Law observes that he wasn’t even the best pitcher on his own team! That shiny “Win” total is clearly the only reason.

The logic is inescapable, but not very useful — you have to look at a number of metrics to make such a judgment about pitchers, not just one. The goal be would to select players that can add as many wins to the team as possible, within a budget.

For those who want to dig deeper into the problem of judging pitchers — and for those who enjoy long descriptions of statistical tradeoffs — and you know who you are — I suggest you read Keith Law’s book (try chapter 14). He actually has an approach to this problem — he calls it “Wins Above Replacement (WAR),” which focusses on an elusive metric: “Runs Prevented.” For me, I skipped to the last chapter where he identifies the two main issues:

1. Baseball provides a lot of data points that are fundamentally interdependent — that is, so few baseball outcomes can be traced to the performance of a single player. It’s a team game (Duh).

2. So much of what drives the way baseball is played and viewed is more cultural than statistical. Players, managers, team owners, and fans do what they do, and like what they like about the game, for reasons they grew up with since the first time each of us was captivated by “baseball fever” when we were kids.

So, when we try to dissect the statistics of the game to understand it better, we find out that baseball is more than it seems . . . and less.

Go Giants!![]()

A Field, In Your Dreams

A Field, In Your Dreams