Archive for Yosemite

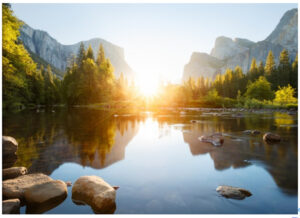

Yosemite — October, 2019

“The dry waterfalls and sparse rivers of Autumn simply provide a promise

for the coming of Spring.

The bright Fall colors are a reminder

of that promise.”

— PapaDan

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

As I’ve written during previous Autumns in Yosemite, this wonderful valley is always changing. The two most prominent features of Yosemite are “Permanence” and “Change.” (See an old ConVivio piece on that subject.) What’s the Peter Allen song — “Everything old is new again.” Yosemite Valley certainly qualifies as OLD — having been carved by a slow-moving glacier beginning about two million years ago, with its sturdiest rocks (e.g., Half Dome) weighing in geologically at about 87 million years. AND as always, it is NEW again à This year, this month, we observed that the Fall Colors are more dramatic than ever (more on that later).

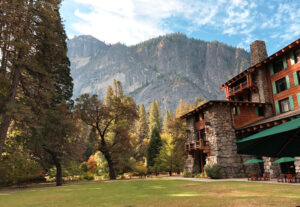

Another piece of Yosemite news in the “Old-and-New” category is that Yosemite National Park has re-acquired its old revered names — the Hotel is now again named The Ahwahnee and Curry Village and Wawona have their names back, as does Yosemite Lodge, and others. I have known these names for fifty years, and they mean something to me. The lawsuit was settled in July after a three-year fight over ownership of the names.

(Talking with a waiter in the Ahwahnee dining room, I observed that the fight was over money. He corrected me and explained, linguistically, that the problem was caused by ‘politics.’ He said, “ ‘politics’ is a word with two parts: ‘poli,’ meaning many, and “tics,’ meaning small blood-sucking creatures.” I expect to use that line again.)

The Ahwahnee Hotel is certainly old by our own standards, having been built in 1927. BUT, what’s interesting to me is this: the name Ahwahnee was given to this part of the valley by the native Ahwahnichi Tribe about 600 years ago — long before the National Park Service or even the United States of America existed. So, the idea that a 21st-century hospitality management company can claim to “own” that name is ridiculous. But now, sanity has been (temporarily) restored (repurchased) and some good old things are new again.

The National Park Service quickly, proudly, replaced the signs.

Yosemite’s Dramatic Fall Colors — October, 2019

We tend to think of the Stanislaus National Forest, where Yosemite is located, as being dominated by evergreen trees like the Giant Sequoia Redwoods, Ponderosa pines, incense-cedar, Sierra Juniper, white fir, and the like. With that in mind, most of us don’t expect there to be much in the way of dramatic Fall colors. BUT, Yosemite Valley is also populated by California Red Fir, various varieties of Hemlock, California Nutmeg, Black Oak, Alder, Birch, Dogwood, Laurel, Big Leaf Maple, Quaking Aspen, Cottonwood, and Willow. All of these punctuate the broad green background with prominent splashes of reds, yellows, golds, blues, ambers, and combinations of those. Here are just a few examples of photos I took just last week in Yosemite:

And The Water — October, 2019

As in Autumns past, one of the most striking features of Yosemite in October is:

The silence.

Unless you visit Yosemite in the Fall, when the waterfalls in the valley are dry, you might not realize how much the roar of Yosemite Falls dominates the sound of the valley in the Spring. When the waterfalls are not running, there is a remarkable silence.

On the left, you can see the place where Yosemite Falls is normally pouring its heart out in the Spring. Here in October — not a drop. The water-scarred granite face of the mountain is bone dry.

Here, you can see the Merced River where it meanders through the valley. Now, in October, it is lower than I have ever seen it and it’s not moving. In the Spring, on the spot Gretta is standing in this photo, she would be standing waste deep in water. Where I am standing to take this photo, I would be ankle deep. We were told that, even though there was a significantly wet winter this year, more of the precipitation came down in rain and fell later than usual. In fact, you can see the hundreds of fallen trees that were brought down this past winter by the flooding. And, a lot of the snow that had fallen melted quicker than usual between Spring and Fall, causing the waterfalls to dry up sooner and the river to recede more than usual.

Looking Ahead to Spring, 2020

Gretta and I also come to Yosemite every April, for our anniversary, and one thing is a constant in April — Yosemite Falls is always flowing with its usual vigor. The sound is not merely of running water, but of chunks of ice and fragments of logs from the high country crashing down on the rock formations between the peak of the falls and the valley floor. All of that — plus the constant rushing of the water — creates a polyphonic orchestration complete with percussion, and you can hear it everywhere in Yosemite Valley from Half Dome to El Capitan to Glacier Point. We’ll be back in six months to see, and hear, the results that we have come to expect.

The climate is changing. We’ll just have to keep monitoring our best gauge of the changing colors and the water — here in Yosemite Valley. It speaks to us. Our task is to watch and listen.

![]()

Reflections On Change — It’s Fall, Right?

“One cannot make the words too strong.”

— Mark Twain

Click here to download a PDF of this post: Its_Fall_Change

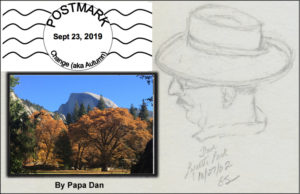

It’s Autumn (aka Fall)

This year, Autumn begins on Monday, September 23 and ends on Saturday, December 21, here in the Northern Hemisphere. During this season, daylight hours become noticeably shorter and the temperature cools considerably. It is also the time when crops and fruits become ready for harvest. In English jargon, over time it has come to be known as The Fall because most leaves fall to the ground and change the color and texture of the landscape dramatically. As a result, all of this change provides great beauty to see in the Fall; and each region has its own style.

Vermont through a windshield—Fall 2013

Now, some people will tell you that you must travel to New England to see “Real Fall Colors.” OK, Gretta and I did that in the Fall of 2013 just to see the colors and — OK — they do know how to do colors in the northeast when Summer turns to Fall. Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, even Maine, did strut some colorful stuff. BUT, while that experience was spectacular, I’m here to tell you (among other things) that you don’t have to travel to the Northeast to see “Real Fall Colors.” Let’s not forget that we live in California.

Now, some people will tell you that you must travel to New England to see “Real Fall Colors.” OK, Gretta and I did that in the Fall of 2013 just to see the colors and — OK — they do know how to do colors in the northeast when Summer turns to Fall. Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, even Maine, did strut some colorful stuff. BUT, while that experience was spectacular, I’m here to tell you (among other things) that you don’t have to travel to the Northeast to see “Real Fall Colors.” Let’s not forget that we live in California.

So, whadda We got?:

— In southern California, the most notorious source of “Fall colors” is the Black Oak, which turns its leaves to a nice golden yellow.

— In northern California, right here in the Bay Area, big-leaf Maple trees are famous for showing off their gigantic deeply reddened leaves before they fall to the ground.

— Farther north in Humboldt County, we see Oregon Ash, Dogwood, Red Alder, White Alder, Cottonwood, and (watch out!) Poison Oak. Each of these is spectacular and, when you can see them all at once … Whoa! … there are no words …

— In Shasta County, especially around Burney Falls, you can see ALL of those plus Vine Maple, Buck Brush, Deer Brush, Red Flowering Currant, and Squaw Bush — all turning from various shades of green to a profusion of reddish, orangish, yellowish, and brownish hues.

— AND THEN there’s the wine country(ies) throughout California, … as the grapes sweeten for harvest and prepare themselves to become the best wine in the world, the vines and ground cover can fill your eyes with multiple shades of greens and reds and even blues and yellows … well … OK, so you’re going to tell me that it doesn’t make sense to try to describe the dramatic changes that happen in the Fall with words, and you’ll be right. AND THEN, you’ll tell me that showing just one picture, or even two, as examples of this phenomenon will fall miserably short of the task. Below — First: Fall Colors in a California Vineyard — Second: And Up Close.

But, well, you gotta look at some colors before we talk about this subject some more.

So, before we continue, you may ask, what exactly is the subject? Is it really about the colors? Or is it about the only constant we can be sure of in this world — change.

Change Is Gonna Come — Oh, Yes It Will

Of course, all of these magnificent colors appear and the leaves fall to the ground because they are dying. Dying. You know, the living things that grow out of the Earth bud and blossom in the spring, they live their lives all summer, and then they die in the Fall. They must die because the trees and vines must shed their growth, spend the Winter in a comatose state — also known as hibernation, suspended animation, … uh … you know, “death” — so they can be reborn and come back to life in the Spring. But, we have to rake up the dead leaves first — And make no mistake, they are dead. Those are the rules.

It’s about change. It’s about change that must happen. But you knew that …

So, We Look to the Poets

Our poets go out of their way to move us past the obvious and convey to us more than the appearance of stunning changes like those we experience in the Fall; they are inspired by the cool fresh air and the end of oppressive inland heat; they celebrate the wonderful produce of all of that struggle (especially in wine country); AND, they also spend some effort marveling at the “terrible beauty” of the cycle itself — birth to life, life to achievement, achievement to beauty, beauty to death, and death to rebirth. Each of these steps must follow from the steps before them. So, often, poets are trying to reveal how all of this inevitable change feels for us humans and what expectations those feelings generate. So, how do we humans experience change?

Let’s ask some of our poets about change, through eyes that view the colors of the season:

- In this one, a young Shakespeare seems to focus on the sense of loss that Fall brings.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold — Sonnet #73 by William Shakespeare

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed, whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourish’d by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well, which thou must leave ere long.

- Next, Robert Frost appreciates the colors of the season, but laments the loss that follows.

Nothing Gold Can Stay by Robert Frost

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

- In her book Time and Place, local poet Lauren de Vore reflects on the responsibility for introspection that comes with the expectation of change. In the chapter on Autumn, her sonnet Taking Stock identifies the change of Autumn as something much more than colors.

Taking Stock by Lauren de Vore

October is my time to introspect,

As like a gleaner following the scythe

I cull through recollection’s field and, eyes

Attuned to see, unflinchingly reflect.

It’s easy to tot up the obvious,

That never-ending list of tasks that should

Be done before the rains arrive and would

Were I, in this, not kin to Sisyphus

Th’intangibles are harder to appraise;

Did I come through for those who needed me?

Did kindness guide my words and honesty

My acts, or did I tread a selfish maze?

One must at times take candid look within

In striving for a life that’s genuine.

- Frank DeRose comes right out and tells us that Autumn is gonna bring important change that will matter very much to us humans, well beyond the colors we see around us.

To Change Autumn is the Season by Frank DeRose

Colors turn,

Leaves fall.

For everything there is a time.

Autumn is a time for change,

A time for being human,

A time to reflect

(On warm summer nights),

And a time to anticipate

(Fiery winter days).

We are human.

Ever-changing,

Ever-moving,

Endlessly.

We are autumnal beings.

Yellow with happiness,

Orange with warmth,

And red with anger.

Red with love.

Red with hatred.

We are as cool

As the crisp breeze,

And as warm

As the colors around us.

To everything there is a season,

For everything there is a time.

A time to lie complacent,

And a time for change.

Autumn is the time for change.

- And our dear old friend Mark Twain brings this Autumnal experience to a close by showing us, entirely with his words, the natural climax of the change at the end of Autumn — words that convey this miracle in ways that a photograph could never do. He shows us the New England ice storm that brings the Fall to its dramatic conclusion. In front of an audience one day, Mr. Twain, rambled on like this (it is my favorite paragraph in all American literature):

— If we hadn’t our bewitching autumn foliage, we should still have to credit the weather with one feature which compensates for all its bullying vagaries — the ice-storm: when a leafless tree is clothed with ice from bottom to top — ice that is as bright and clear as crystal; when every bough and twig is strung with ice-beads, frozen dew-drops, and the whole tree sparkles cold and white, like the Shah of Persia’s diamond plume. Then the wind waves the branches and the sun comes out and turns all those myriads of beads and drops to prisms that glow and burn and flash with all manner of colored fires, which change and change again with inconceivable rapidity from blue to red, from red to green, and green to gold — the tree becomes a spraying fountain, a very explosion of dazzling jewels; and it stands there the acme, the climax, the supremest possibility in art or nature, of bewildering, intoxicating, intolerable magnificence.

One cannot make the words too strong. — Mark Twain

So much for the changes that Fall brings. Along with all of these features, the coming of Fall can remind us humans, at least subconsciously, of the other kinds of change we come to expect — if we are optimists — or the kinds of change that we want to see, that we hope for, that we desperately need to see, that we may fear are out of our reach, as we look around at the disappointing world of the time in which we live.

- Among our poets, songwriters have expressed some of our deepest feelings. Speaking for many of his time (late 1964) and of our own who have grown up in hard times, San Cooke wrote a song that never quite made it to the top of the charts, but still insisted on optimism:

A Change Is Gonna Come by Sam Cooke

I was born by the river in a little tent

Oh and just like the river I’ve been running ev’r since

It’s been a long time, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

It’s been too hard living, but I’m afraid to die

‘Cause I don’t know what’s up there, beyond the sky

It’s been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

I go to the movie and I go downtown

Somebody keep tellin’ me don’t hang around

It’s been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Then I go to my brother

And I say brother help me please

But he winds up knockin’ me

Back down on my knees, oh

There have been times that I thought I couldn’t last for long

But now I think I’m able to carry on

It’s been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will

Experience Teaches; and We Must Learn

So, those of us who look around and see so much that needs to change, so many who desperately need those changes, and so many obstacles stacked up against those changes — what’s a person to do? It seems increasingly clear that it will not be enough to be an optimist, like Sam Cooke, and rest assured that “Change is gonna come — yes it will.” So, we wonder if there are things that some of us urgently need to be doing to bring the changes that the seasons will not bring on their own? Once again, we are reminded of the words of Edmund Burke:

“All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”

A poet of our own time gave us some further advice: “BE the change you seek,” he said. So, we know from the experience of the Fall that change is inevitable. Nothing stays the same and for very good reasons. Some things must die to make way for other things that must arrive. But must we just wait for it like Sam Cooke? Edmund Burke taught us long ago that is the worst thing we can do, and history has proven him right. We can look around and see that some people are MAKING change happen that is seriously evil while we watch — change that unravels progress we thought we had made. Positive changes we thought would endure in the way humans treat each other are reverting to hatreds we had hoped were diminishing. Opportunities for people to raise their standard of living are receding before our eyes in our country — and we see people in power making that happen by their words and actions. Must we merely wait and watch them do their damage and hope for the best? OR, does the optimism of San Cooke carry responsibilities with it to change the course of change itself?

It happens in nature as well as in human behavior. In a world with a warming climate, the changes that come at the end of Fall will be disastrous — we can see it happening if we are paying attention — the necessary ice melts; the rainfall floods the fields instead of nurturing the crops; the bees required to pollinate everything are dying out; the colors are different.

The hard truth is that we know why those things are happening. We know which industrial human behaviors are causing those changes. Yes, it turns out that actually can control the change. If we just wait and watch, others will control the outcome. Some are actually valuing dollars ahead of human survival. How can we make change happen that we need, instead of allowing others to dictate the destructive changes that we can see coming? There’s work to do. We do need to BE the change we seek.

We’ve learned that we are not likely to be successful acting alone. We’ve been told — it takes a village; it takes unions; it takes a unified political party; it takes a committed nation, it takes partnerships and alliances that cross all kinds of borders. Forces that divide and impede our collective efforts must be recognized for the harm they bring and must be defeated. These are hard words; but they are the lessons we have learned.

So, Fall is the time to take stock of our behavior and take responsibility for the effect we have on the direction of change. We have seen what happens when we do nothing. It is not a mystery. We must help each other survive the Winter and bring on the Spring.

![]()

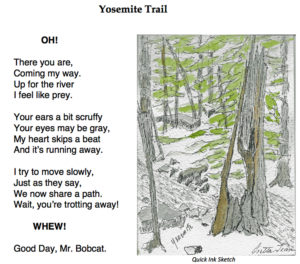

Poetry and Plein Air

By GrettaJean

Click here to download a PDF of this page: Poetry_Plein Air_YosTrail_Bobcat_FINAL_lite

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

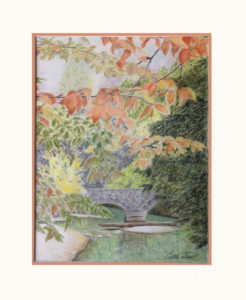

Art & Ideas: Art by GrettaJean

Yosemite in the Fall — 2017

— Pastel drawing by GrettaJean

ConVivio_Yosemite in the Fall_GrettaJean

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Yosemite: Change Revisited

“It is easier to feel than to realize,

or in any way explain, Yosemite’s grandeur.”

— John Muir

“What a treasure to pass on . . .

(but make sure you bring your lunch).”

— PapaDan

Click here to download a PDF of this post:Yosemite, October 17, 2017

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Yosemite, October 17, 2017

Sitting here in the middle of a meadow, looking up at Yosemite’s venerable Ahwahnee Hotel, it seems different in some way. Since you probably know some of the history of this place, you may ask with raised eyebrow and derision in your voice “Aw-come-on-now, what could possibly be different?” You might point out a few things like: the iconic stone-and-wood edifice in front of me has looked pretty much the same since it opened in 1927; the granite mountain, El Capitan, to the left of this view has looked much the same for, oh, 50,000 years or so; and the squirrels and blue jays who live here have been scurrying and squawking like this since the glacier melted — so, what could possibly be different?

Sitting here in the middle of a meadow, looking up at Yosemite’s venerable Ahwahnee Hotel, it seems different in some way. Since you probably know some of the history of this place, you may ask with raised eyebrow and derision in your voice “Aw-come-on-now, what could possibly be different?” You might point out a few things like: the iconic stone-and-wood edifice in front of me has looked pretty much the same since it opened in 1927; the granite mountain, El Capitan, to the left of this view has looked much the same for, oh, 50,000 years or so; and the squirrels and blue jays who live here have been scurrying and squawking like this since the glacier melted — so, what could possibly be different?

I’ll have think about it — you’ve asked a big question that demands a big answer; but I, of course, have a small answer:

—> It’s quiet. Nearly silent, actually. THAT’S what’s different.

Gretta and I come to Yosemite every April, for our anniversary, and one thing is a constant — Yosemite Falls is always flowing with its usual vigor. The sound is not merely of running water, but of chunks of ice and fragments of logs from the high country crashing down on the rock formations between the peak of the falls and the valley floor. All of that — plus the constant rushing of the water — creates a polyphonic orchestration complete with percussion, and you can hear it everywhere in Yosemite Valley from Half Dome to El Capitan to Glacier Point.

But, in October (for our second yearly visit), North America’s tallest waterfall is completely dry.

And silent. And, the silence of October is more noticeable than the sound of April.

Upper Yosemite Falls (April) Upper Yosemite Falls (October/Dry/Silent)

But, before I claim that everything else around here is permanent, I come to realize that much has changed, and is changing all the time. Some of it matters, and some doesn’t.

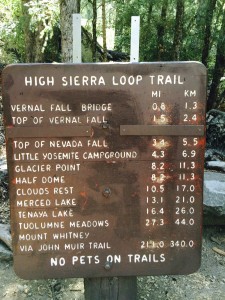

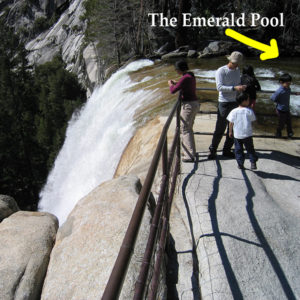

The Water

• The water that feeds the Merced River from the opposite side of Yosemite Valley, across from Yosemite Falls (see the images below), originates at the granite dome of Liberty Cap, thunders down at Nevada Falls, sits awhile in the Emerald Pool, rumbles down at Vernal Falls, and ends up meandering through the valley floor in the Merced River. As the seasons change, that river trickles between the boulders at its low point here on October and then swells to a wide, white-water torrent in April. So, at least that much changes; but a wise observer might point out that all of this ebb and flow, the meandering and the raging, the silence and the music of the falls form a never-ending constant cycle in their seemingly eternal alternation between the extremes of life in this valley among these mountains. Yosemite has been here a very long time — longer than the life-span of humans on this planet — and the forces at work here seem to be eternal; BUT those forces are carving a work of art. Each time you look, if you are paying attention, it never looks quite the same as it did the last time you looked.

Nevada Falls Top of Vernal Falls/Emerald Pool Vernal Falls

The Granite

• Today, El Capitan slopes at a slightly different angle since last month when a slice of granite the size of an apartment building cracked and crashed down on one of its outcroppings and scattered giant boulders, many the size of automobiles, around its base. Rock falls happen all the time in Yosemite but they are seldom fatal (as this one was) and often not especially noticeable — unless you consider that this entire valley and its surrounding mountains were carved and shaped over thousands of years in precisely this manner. So, Yosemite changes its shape pretty much everywhere you look and pretty much all the time.

The Colors

The colors speak for themselves. BUT, some of us have tried to speak for them — and maybe overdone it in the attempt, or not – like our old friend Mark Twain who tries to give us a glimpse, in words, of trees in the fall that change “from green to red, from red to green, and green to gold. The tree becomes a very explosion of dazzling jewels; it stands there, the acme, the climax, the supremest possibility of art or nature, of bewildering, intoxicating, intolerable magnificence. One cannot make the words too strong.” Or so he said.

Twain’s words appeared in the New York Times in 1876, not as evidence of change, but as evidence of permanence — describing something that has been repeated every year since long before humans were here to observe it. And here, now, in Yosemite, we see it once again.

Trivial Change

Now, if we’re going to make a list, some things HAVE changed here in Yosemite, just in the decades we have known it; but those are caused by humans and, therefore, less important:

• The Ahwahnee Hotel has been renamed The Majestic Yosemite Hotel. Why? — because the previous management of the hotel claims to “own” the name “Ahwahnee” after a coupla decades of association with it. The silliness of that view comes to light when you consider that the hotel was named for the Ahwahneechi Tribe who were associated with this part of the valley since about 600 years ago — long before the United States National Park Service granted a contract for restaurants and hotels (OK, long before the United States existed). So, Gretta and I still call it by its rightful name — The Ahwahnee Hotel.

• The Ahwahnee cocktail lounge, which used to serve excellent food all day long, now serves, well … OS (i.e., other stuff). We tried it for breakfast this time … I didn’t know it was possible to screw up yogurt and granola, but now I know. It has been our habit to enjoy a cocktail and tasty appetizers here in the late afternoon. The “cocktail” part endures as it should but the “tasty appetizer” notion is missing. It also used to feature a delightful piano player in the evening (he played everything from classics to smooth jazz to show tunes to classic rock — request almost anything, he knew it). Now the piano is gone to make room for three more tables and a sound system plays, well … OS.

• The Ahwahnee main dining room used to be a 5-star restaurant that attracted outstanding chefs. Now it is just a lovely high-ceilinged, grand building with an OK restaurant surrounded by breath-taking views, pouring from a mediocre wine list, and serving … well, you know, OS. It isn’t even the best restaurant in this valley.

• Oh, and there’s Degnan’s Deli, which used to be an ideal spot to interrupt a day of hiking by ordering a hand-made sandwich, salad, or soup, crafted with fresh ingredients. Now, it is dominated by a display case full of pre-packaged “gas-station-sandwiches.” And they’ve innovated: you can stand in line to order and pay using computerized kiosks and then stand in another line to pick up your order. This “innovation” succeeded in eliminating four employees who used to make your lunch to order from fresh ingredients and take your money at enough cash registers to avoid standing in line. You can still sit at their outdoor stone tables looking up at a stunning view of Glacier Point, but … my recommendation is that you bring your own lunch. Yes, it’s changed.

So, now I’ll stop whining

and tell you why we must continue to return here twice a year.

We come back for the many wonderful things that remain the same here in Yosemite Valley. Here are a few of those in the words of some of our friends:

• Words from Teddy Roosevelt: “There can be nothing in the world more beautiful than the Yosemite … and our people should see to it that [it] is preserved for their children and their children’s children forever, with [its] majestic beauty unmarred.”

• Words from John Muir: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. As age comes on, one source of enjoyment after another is closed, but nature’s sources never fail.

• John Muir again: “It is easier to feel than to realize, or in any way explain, Yosemite’s grandeur. The magnitudes of the rocks and trees and streams are so delicately harmonized, mostly hidden.”

• Frightening words of warning from NYT columnist Nicholas Kristof: “I can’t help thinking that if the American West were discovered today, the most glorious bits would be sold off to the highest bidder. Yosemite might be nothing but weekend homes for internet tycoons.”

• Words from Robert Redford: “I spent two summers working at Camp Curry and at Yosemite Lodge as a waiter. It gave me a chance to really be there every day – to hike up to Vernal Falls or Nevada Falls. It just took me really deep into it. Yosemite claimed me.”

• Words from Dave Brubeck: “I used to take my mother to Yosemite. When got my driver’s license, that’s where she’d want to go, so I’d go take her there for two weeks.”

• Words from John Garamendi: “Maybe you weren’t born with a silver spoon in your mouth, but like every American, you carry a deed to 635 million acres of public lands. That’s right. Even if you don’t own a house or the latest computer on the market, you own Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and many other natural treasures.”

• Words from Ansel Adams: “Yosemite Valley, to me, is always a sunrise, a glitter of green and golden wonder in a vast edifice of stone and space.”

• More from John Muir: “During my first years in the Sierra, I was ever calling on everybody within reach to admire them, but I found no one half warm enough until Emerson came. I had read his essays, and felt sure that of all men he would best interpret the sayings of these noble mountains and trees. Nor was my faith weakened when I met him in Yosemite.”

• And, finally, from PapaDan: “Some years, one or more of our sons bring their families up here during the same week we visit, and we have the privilege of taking our grandchildren to the bank of the Merced River (below, left) or up to the base of Yosemite falls (below, right) and watch them enjoy the spectacle in amazement. What a treasure to pass on to the next generation!”

We’ll be back in April!

If you’re interested, click to take a look at a previous post on this topic:

“Of Permanence, Change, and a Sense of Wonder“

Yosemite: Of Permanence, Change, and a Sense of Wonder

Even (maybe especially) after a few dozen visits to this magical place, a powerful sense of wonder is always present. I am sitting near the back of the Ahwahnee Hotel’s Great Room in Yosemite Valley, accompanied by the family artist (Gretta), a glass of Sonoma County Pinot Noir (from Flowers Winery), and an iPad; my eye drifts up to the gigantic ceiling, built in 1927 and festooned with an Ahwahneechi tapestry, woven deep red, blue, gold, and black, above the six-by-ten-foot fireplace and illuminated by four immense iron candelabra, electrified only in recent decades.

Even (maybe especially) after a few dozen visits to this magical place, a powerful sense of wonder is always present. I am sitting near the back of the Ahwahnee Hotel’s Great Room in Yosemite Valley, accompanied by the family artist (Gretta), a glass of Sonoma County Pinot Noir (from Flowers Winery), and an iPad; my eye drifts up to the gigantic ceiling, built in 1927 and festooned with an Ahwahneechi tapestry, woven deep red, blue, gold, and black, above the six-by-ten-foot fireplace and illuminated by four immense iron candelabra, electrified only in recent decades.

The view from here, positioned behind two thickly covered grand pianos, speaks of enduring elegance, respectfully built on ancient Native American roots, offered here for those who would take their place where presidents, magnates of industry, backpackers, and parents with children on Spring Break have quietly relaxed since before anyone knew there would be either a Great Depression or Great Recession from which to recover. A crew of uniformed servers quietly prepares the afternoon tea-and-cookies service for those who drift in from their day in the woods.

From recent experience, I know that the grandest of the pianos will be uncovered soon, to be employed with the collaboration of Mozart and others to set a mood that alternates between quiet contemplation and festive revelry. Remarkably for those of us mired in the 21st century, the wood-carved sign at the entrance to this Great Room, reminding those who enter to be on their best behavior, is respected and obeyed, evident in the obviously coached youngsters who speak in hushed (for them) tones as they enjoy surroundings that even they know deserve some respect.

From recent experience, I know that the grandest of the pianos will be uncovered soon, to be employed with the collaboration of Mozart and others to set a mood that alternates between quiet contemplation and festive revelry. Remarkably for those of us mired in the 21st century, the wood-carved sign at the entrance to this Great Room, reminding those who enter to be on their best behavior, is respected and obeyed, evident in the obviously coached youngsters who speak in hushed (for them) tones as they enjoy surroundings that even they know deserve some respect.

Today is a surprise. Yosemite has not been immune to the ravages of California’s four-year-and-counting drought, demonstrated by weaker-than-usual waterfalls, above-average temperatures, and NO recent snowfall. But today, April 5th, is different — today we all woke up to falling snowflakes as big as cottonballs and the low temperatures that Yosemite’s regular visitors had come to expect this time of year. So, the snow clothes and smiling faces began gathering in front of the giant fireplace by mid-afternoon.

Precisely at four, a well-dressed gentleman arrives, wheels in his own particular chair, uncovers the piano, becomes comfortable before the keys, and changes entirely the color and flavor of the giant room, using his own particular brand of concentration, without need of sheet music. Activity in the room, however, does not change — gentlemen wearing baseball caps still relax on colorful sofas, dads in snow clothes still wheel baby strollers into the space in front of the fire, accompanied by moms directing toddlers and school kids to their appointed places to divest themselves of wet clothes, carefully hung to dry on the hearth, revealing the activities of the season — gloves and mittens that had been throwing snowballs, stocking hats that had kept ears warm but not dry, boots that had been crunching across the first (and last?) thick snow of Spring, and snow pants that had been crawling on the snow as the older children rolled big balls of ice to create the torsos of snowmen. The music rises to the rafters, not needing volume to command the attention of the room, but not interrupting the business of families doing what they came here to do.

Chopin makes an appearance, again without benefit of sheet music – the gentleman lost in his own enjoyment — not limiting himself to the first movements of pieces most may recognize, but retelling masterworks in their entirety. The room is now filled with the dual majesty of the music inside and the mountains outside. People from multiple generations, classes, and ethnicities read their books, discuss their topics, sip their teas and wines, draw their pictures, and yes, write their words — all under the watchful eyes of Half Dome and Yosemite Falls, peering in through the high windows on opposite sides of this magnificent room.

The multiple personalities of the Spirit of Yosemite make their presence known, even through those high windows — Half Dome, out one window, stands as a dark chocolate truffle, sprinkled with powdered sugar that someone cut in half to see if it’s the one with a raspberry inside. It’s not, but worth the cut to find out. Out the opposite window, Yosemite Falls, diminished in volume by a drought-ish and warm winter, pours its modest goodness into a splash of mist just visible between tall, straight evergreens and bare, spreading oaks.

Tchaikovsky appears, as does sheet music for the first time, as a young girl slides up to look over the gentleman’s shoulder at the piano. She steps progressively closer as the music gets more animated, eyes wide, alternately staring at the sheet music and at hands on the keys, all the while bouncing with her hands and arms, revealing some experience of her own at the keyboard. At the end of the piece, he leans back, points at the sheet music, and says to the girl, “Look. It’s not that hard. You could do it.”

Tchaikovsky appears, as does sheet music for the first time, as a young girl slides up to look over the gentleman’s shoulder at the piano. She steps progressively closer as the music gets more animated, eyes wide, alternately staring at the sheet music and at hands on the keys, all the while bouncing with her hands and arms, revealing some experience of her own at the keyboard. At the end of the piece, he leans back, points at the sheet music, and says to the girl, “Look. It’s not that hard. You could do it.”

This is, of course, just a snapshot, a small glimpse in time and space. We can wander from this room to stand before — or even atop — other great natural wonders of our continent: Vernal and Nevada Falls, Mirror Lake, the Merced River, Glacier Point, and rock faces carved by forces we humans cannot duplicate and that we do not live long enough to witness in our collective lifetime on this planet. A snapshot is all we have ever seen; but we continue to imagine the part of the snapshot cropped out of our view, before and after the time and space we occupy.

Why do we come here? Is it for the mountains – appearing larger and more permanent than anything that has surrounded us anywhere else? Or is it the water — to see what it can do when it arrives with power from far above us? Do we come here to be in the presence of creatures — bears and deer, birds and coyote, and their compatriots — not familiar in our neighborhoods back home? Maybe, without realizing, we come to experience the simultaneous work of permanence and change: two illusions who conspire to fool us into thinking we understand the rhythm of this life, only to surprise us by revealing things and ideas hiding in plain sight, that have always been there waiting for us to discover them anew. Are we proud to see that we can erect what we believe to be enduring human elegance, like this grand hotel, amid the seemingly transitory elegance that pours out of the granite for moments and is then gone — over and over, across millions of years that we believe we can count but can really only imagine? Do we come here to listen to the voices that remind us that the things we consider ‘permanent’ are not so permanent to Yosemite — that permanence and change might just be two sides of the same stream? Do we come here to escape the hopelessness we read in the newspaper, which I am reminded to put away when I enter this cathedral of nature? Does our presence here expose a glimmer of hope that parents still bring their children here — as an investment in the future? Perhaps it is that same ever-present sense of wonder, with which I arrived, that brings me back and back again.

Yosemite — A Place to Stand, A Moment To Savor

Yosemite Valley, California — Thanks to the foresight, eloquence, and hard work of people like The Ahwahneechee, Galen Clarke, and John Muir, the unmatched beauties of this valley can be easily accessible to most of us. But, there are some particularly intriguing views of it that require a bit of struggle. That is fair, of course, given the immense struggle — 20 million years of artful carving by a persistent glacier — that nature endured to form this valley.

On this particular day, Gretta and I are sitting next to a 100-foot tall pine tree in the middle of a meadow about 50 yards from the Ahwahnee Hotel and its five-star dining room. Directly in front of me, Yosemite Falls pours its heart out as it has done since long before human beings stared up in wonder and gave it a name. This magnificent view, one of Yosemite’s most famous, is easy to enjoy — just a three-hour drive from the Bay Area and a five-minute walk from a parking lot to this meadow.

But on Tuesday of this week, we selected a more ambitious project. For decades, I have held a particular admiration for a pair of Yosemite’s less accessible waterfalls — Vernal and Nevada Falls. A pleasant 45-minute walk from the “Happy Isles” bus stop to the wooden bridge across the Merced River allows a hiker to look up at the view of Vernal Falls that Ansel Adams captured in a well-known photograph. That is surely worth the easy hike. But ever since the first time I set foot on that bridge, something has called audibly to me, in a voice from the top of that waterfall. From that first time, it has been clear that the real thrill, and the real achievement, would be to seek out the top of the falls — and a spot from which both Vernal and Nevada Falls are both visible and both audible.

There are two ways to reach the top of the falls from the bridge. One is the direct approach: a sharp left turn after the bridge and a 30-minute climb up what is called the “Mist Trail.” This trail is named for its stairway that climbs alongside the falls — close enough to feel the mist from the falls. This slippery path is most suitable for mountain goats and the most intrepid, sure-footed humans. I took this path years ago when youth and lack of fear gave me confidence that I could reach the top without slipping down the shear rock face to the boulders below. We did not take this path on Tuesday.

The other way is to turn right after the bridge and follow the John Muir Trail on a long winding path around behind the mist trail to the top. We took this path on Tuesday — it is known to be an easier, safer climb.

OK, so let’s define “easier.” For us, this walk entailed four hours of up-and-down switchbacks and narrow ice-filled ledges, some requiring crawling on our hands and knees in the snow.

The hike up the mountain was not exhausting, but invigorating, as each turn brought into view a new and spectacular look at the mountain above us and, looking back, an ever-broadening look at the Yosemite Valley we were climbing out of. However, with each passing hour, we reminded ourselves that each step UP the mountain would have to be repeated later on the way down. Our judgment seemed reasonable each time we said, “Well, it would be a shame to come this far without getting to the top.”

So, at long last, one of the turns in the trail rewarded us with the moment we were seeking. Stepping out on a large boulder we looked DOWN at the roaring top of Vernal Falls (as seen in the photo at the top of this essay) and looked UP at its source: gigantic Nevada Falls (below). What a sight! What a place to stand! What a moment to savor!

Nevada Falls

At moments like this, I realize that my most memorable travel experiences have consisted of savoring moments when I have reached a wonderful place to stand — memorable for a range of reasons, from historical significance, to man-made beauty, to sheer natural wonder, like this one. Click here to see and hear a few seconds at the top of Vernal Falls: Top_Vernal_Falls.AVI

The exhilaration of standing on this spot was slowly overcome by a new logic: since it took four hours to get here, it would surely take four more hours to get back. Fear of darkness and the hungry wildlife it would bring out cast a fairly formidable shadow in the bright sunlight of this moment. And, as we began our descent, the aches of already-sore muscles began to make the task ahead seem more and more intimidating with each new switchback and icy ledge. After four hours of uphill and three hours of downhill, the realization emerges that downhill can be much more difficult than uphill for sore muscles and tired feet.

Our twilight arrival at the valley floor was an overpowering mixture of relief and pain. Had this been a good idea? Had we gone too far? I can hear the answer in the voice of the rushing water that called us to that spot above Vernal Falls: “Come and join the beauty, it is worth the struggle.”

It was. ![]()