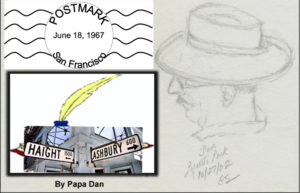

“The Summer of Love” — 1967

“The Summer of Love” — 1967:

More Than A Summer

“Do you believe in Rock & Roll?

Can music save your mortal soul?

Can you teach me how to dance real slow?”

— Don McLean (from “American Pie”)

Click here to download a PDF of this post: ConVivio_Summer_1967_V2

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

The Music of My Generation

The great music of my generation reached a climax in 1967. That historic musical moment — widely recognized as the pinnacle of the music of my generation — “warmed up” around 1962-5, reached its peak in the “Summer of Love” of 1967, and culminated in the last few years of the sixties leading to the grand finale: “Woodstock” in August of 1969.

Since most of my generation was in high school at the time, we tend to think of “1967” as the school year that began in the fall of 1966 and ended late in 1967, when my friends and I settled into our senior year. Of course, nothing of cultural importance begins and ends that abruptly and crisply, so we will consider those dates to be approximate. For most of you “of a certain age,” these details may not be new, just reminders of a time in your own life.

It Started With Something New: Buying Records

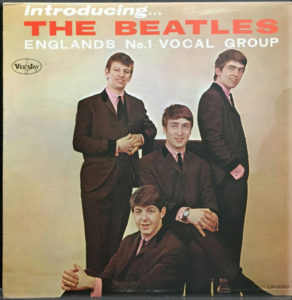

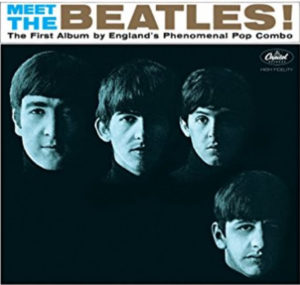

I began buying vinyl records in 1964, starting with the purchase of my first Beatle album, “Introducing the Beatles,” in January (I still have it) followed a couple of weeks later by “Meet the Beatles” (my son Ben has it). This was an important milestone in my teenage life and the act of buying records quickly became a four-step ritual for me. Here was the pattern:

Step 1. I would hear something exiting on the radio played by one of the two important disc jockeys in the bay area on KYA:

— “Emperor” Gene Nelson was “The Emperor” because his loyal following carried “Royal Commando” cards, he issued his own royal currency (accepted only within “The Empire”), and counted down the “Top Thirty” every Saturday morning.

— “Big Daddy” Tom Donohue advertised acne creams and opened his show with the line: “This is your Big Daddy Tom Donohue. I’m here to clear up your face and mess up your mind.” He co-produced the Beatles last public appearance at Candlestick Park August 29, 1966. About this time, a friend turned me on to something new: FM Radio! KSJO in San Jose played music and said things that could not be heard on AM radio. Tom Donohue pioneered “album-oriented” radio at KMPX FM. We called these FM stations “underground radio.” (Our parents did not listen to these stations.)

Step 2. I would walk uptown to the record store (Don McLean later called it “The Sacred Store” in his classic song “American Pie”). I would ask the lady behind the counter if I could listen to a particular song. She would play it on a turntable if it was on a 45-RPM single (99 cents); but she wouldn’t play an album. In the case of an album, I would inspect the album cover and put it back in the rack for later consideration (albums cost more — initially, a dozen songs for $2.99.

Step 3. After due consideration (usually a day or so), I would walk back to the record store and buy the album (except in the case of a Beatle album — in that case I would have bought it immediately, without question, the first day it was released.

Step 4. As soon as I got home, I would play the entire album from beginning to end without delay or interruption, making judgments about which songs were “hits” and deciding if I preferred one side over the other. Sometimes a friend joined in this part of the ritual. In many cases (again, except for the Beatles) I ended up playing the preferred side almost exclusively after making that judgement.

My Dad encouraged me to buy records, as he had done. I still have his 78-RPM recordings of Cole Porter, Dale Carnegie (“How To Win Friends and Influence People”), and Red Motley (“Nothing Happens Until Somebody Sells Something”), and the soundtracks I heard growing up: “Carousel,” “My Fair Lady,” “Camelot,” and a little classical and opera. I don’t think he really understood my music, but I think he figured that it didn’t do any harm.

Most popular songs, especially in the early sixties, were released on 45-RPM “singles,” with a “hit” song on one side — the “A” side — and usually a throw-away song on the “B” side that would seldom be heard on the radio. The Beatles broke that mold by releasing singles with great songs on both sides. These were almost uniformly three minutes long until July of 1965 when Bob Dylan released “Like a Rolling Stone,” which was more than six minutes long. At first, radio stations played a truncated version; but it quickly became a world-wide hit, broke through that constraint, and we heard it on the radio in its entirety. Why was it such a big deal? Even though it wasn’t particularly ‘musical,’ its “street poetry” described some of the familiar experiences of many young people of my generation and then asked:

“How does it feel?

To be on your own,

with no direction home,

a complete unknown,

like a rolling stone.”

It seemed to touch something deep in the hearts of young people experiencing in the strangeness of growing up in the second half of the 1960s. There would be more to come.

So, What Records Did I Buy?

I bought a few singles; but, after a while, I stopped buying singles and stuck with albums. This change coincided with the trend among popular musicians starting around 1965-66 to record an entire album of their best songs, several of which were “hits” that might have been played on the radio. So, albums contained a lot more storytelling and developed more important themes than songwriters could convey in one three-minute song. Many of the songs of the time reflect the ideas and feelings that mattered to so many of us during that period.

Below is a link to a PDF list of the record albums released during this time that I bought then or over years that followed. It turns out to be a pretty good indicator of what was popular among teenagers, at least in my high school at the time. AND it serves as the musical content that led to the “Summer of Love” in 1967 and other major music events of 1968-9. I bet many of you had these same records or at least remember hearing many of them, either at that time or later –>–>–> AND I’d love to hear from you about the music that was important to you during this time, whether you were alive then or not — since many of you grew up listening to your parents’ records of these songs that they continued to play in later years (as I did).

Records I bought from 1964, with release dates (underlined titles are links):

Click here: Dans_Records_1964-1968.pdf

What actually happened during 1967?

The term “Summer of Love” originated with the formation of the “Council for the Summer of Love” in the spring of 1967 as a response to the convergence of young people on the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco. The Council was composed of The Family Dog, The Straight Theatre, The Diggers, The San Francisco Oracle, and approximately twenty-five other people, who wanted to plan for the influx. The Council also assisted the Free Clinic and organized housing, food, sanitation, music and arts, and coordinated with local churches and other social groups. So, there was some preparation.

- January 14 The Human Be-In takes place in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco; setting the stage for the “Summer of Love.”

- January 28 – The Mantra-Rock Dance, called by some the “ultimate high” of the hippie era, takes place in San Francisco, featuring Swami Bhaktivedanta, Janis Joplin, The Grateful Dead, and Allen Ginsberg.

- June 16-18 – Most consider the three-day Monterey Pop Festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds to be the focus of “The Summer.” That event — fifty years ago this week (celebrated last Sunday) — brought together thousands of people to see and hear many of the most well-known rock & roll musicians of the era — notably, The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, David Cosby, The Who, The Association, The Doors, Hugh Masekela, Grateful Dead, Country Joe and the Fish, Janis Joplin (Big Brother and the Holding Company), Eric Burden (Animals), Otis Redding, Simon & Garfunkel, and The Mamas & the Papas. The event essentially launched careers of some performers who had not yet achieved national recognition — Janis Joplin, Laura Nyro, Canned Heat, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar, and Steve Miller are examples.

Some notables intended to perform . . . but:

— The Beatles decided that their music had become too complex to perform live and did not perform (and never toured again).

— The Beach Boys, although Brian Wilson was a leader in the planning of the event, decided not to perform — perhaps their music came out of a different mindset (surfing and fast cars) and didn’t quite fit into this particular “Summer.”

— Donovan, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, among others, couldn’t get visas to enter the US because of drug arrests.

— Dionne Warwick had a conflicting gig at The Fairmont in San Francisco.

— Bob Dylan declined because he was still recovering from his motorcycle accident. (Hendrix paid tribute to him by performing “Like a Rolling Stone.”

— Frank Zappa (Mothers of Invention) refused to share the stage with SF performers he considered to be inferior. (Huh?)

— Organizers rejected some who asked to perform, like The Monkees (thanks); and some (like Cream) backed out hoping to perform in a venue that would provide “more exposure” (ooops!).

Other cultural/musical events took place around the world in places like New York, London, and elsewhere; and — related — on October 17, the musical “Hair” opened off-Broadway on October 17 and moved to Broadway the following April. But “That Summer” also featured a number of distressing public events. It was a difficult time in America: several large and violent anti-war demonstrations did serious damage that summer and several multi-day race riots erupted in Tampa, Buffalo, Newark, Plainfield, Minneapolis, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Washington DC, leading to more than 100 deaths and significant disruptions in communities and colleges across America. So, there was more going on than just the music.

Was It Just the Prelude?

Most would say that “The Summer of Love” was the focal point of the development of the music of the time; BUT, as an event, most say it was just the prelude leading up to the central musical event of my generation. “Woodstock” took place August 15-18, 1969, on at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm near New York and was attended by over 400,000 people and millions of us will claim “I was there.” (I was, uh, there.) BUT, if you look at the music that was performed at Woodstock and the musicians who performed, I think you’ll agree that the music emanated from the inspiration of 1967. We can save THAT topic for another time. The cultural event had its own significance. For the purpose of remembering “The Summer of Love,” it was all about the music.

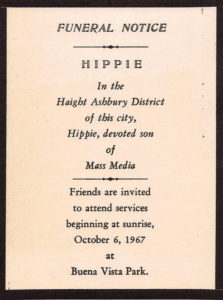

And, Yes, It Had a “Funeral”

After many people left at the end of summer to resume their college studies, those remaining in The Haight wanted to commemorate the conclusion of the event. A mock funeral entitled “The Death of Hippie” was staged on October 6, 1967. Organizer Mary Kasper explained the message:

“We wanted to signal that this was the end of it, to stay home, bring the revolution to where you live, and don’t come here because it’s over and done with.”

Mock Funeral Notice

But the Music Didn’t Die

Life got tougher in America: the Vietnam War became more intense, as did protests against it, a cultural divide opened between generations, and the assassination of Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sparked riots across America. BUT — the music didn’t die. We bought the records, listed on the radio, our children heard those records growing up in our homes, and — after these fifty years have passed, the songs of that era continue to be popular landmarks in music, culture, and literature.

![]()

You make an important point: the music didn’t die. If anything, worsening times made for better music. This is the main reason I’ve never liked “American Pie”. I don’t accept its central thesis.

Steve, Thanks for reading. Don McLean tells some important parts of the story of the music and the times; but you’re right — the music was stimulated by the increasing difficult times and did not die. The stream of images in his song carry a lot of cogent memories (the “sacred store, where I heard the music years before,” my beloved “Marching Band” that refused to yield,” and others) so, I think it is a legitimate reference. Of course, his song comes AFTER the music leading up to 1967/68, which, I claim, is the pinnacle of our musical and cultural heritage. What albums would you add to my list from those years?

I found it amusing, charming, not quite sure the correct adjective, to listen to my teen-aged son (now in graduate school) discourse on the Beatles and classic rock and roll, often informing me of various who-s, what-s, and when-s. I would smile and (only sometimes) remind him that “I was there.”

Yes, I am pleased that many of the (now grown) children of people like us who “were there” have been educated in the music of that time. I am proud that my sons also “were there then.”

Getting back a bit late :-). Albums I might add:

The Velvet Underground and Nico

Aretha Franklin: I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You

Jefferson Airplane: Surrealistic Pillow

Steve,

Yes, Surrealistic Pillow is one of the classic 1967 albums I bought that year. Grace Slick (from that album) still rocks.

Dan