Looking Back One Hundred Years

‘When’ and ‘Where’ Are Easy, But ‘Why’ and ‘How’ Are Tougher

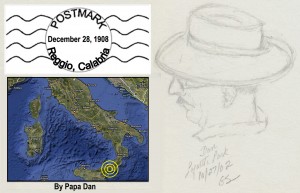

One hundred years ago — 101 to be exact — my grandfather Antonio, and his wife Maria, left Reggio Calabria, at the toe of Italy’s boot, sailed out of the Mediterranean, crossed the Atlantic, entered New York Harbor, and landed on Ellis Island to begin a new life in America.

By itself, this is not an unusual story. Tens of thousands of Italian immigrants made the same journey during the first decade of the 20th century, many more from Southern Italy than elsewhere. The population of Italian immigrants on the eastern seaboard of America, notably New York and Boston, swelled to a point where, in 1910, more native Italians lived in New York City than in the Italian cities of Florence, Venice, and Genoa combined. A popular expression in Southern Italy was: “Chi esce riesce (He who leaves succeeds).”

I had heard bits and pieces of the story all my life — how Antonio, who was illiterate in two languages, couldn’t make himself understood well enough to communicate his own name. When the only job he was able to get was in a coal mine in Red Jacket West Virginia, he was known, and paid, as Tony Sabo. My father and his brothers later learned that wasn’t their name.

He had been part of a Calabresé family who grew citrus and grapes and made wine and, apparently came to America to do the same. According to the family story, Antonio was at a grocery store in Huntington — the town next to Red Jacket — depressed that he had left behind farming and wine-making to work in the coal mine, asked the Italian-speaking shopkeeper, “Where did this orange come from?” The answer determined his future and the future of my father, myself, my sons, and their children. The shopkeeper said, “California.” Antonio replied, we are told, “I am going to California, my boys are not going to grow up in the coal mine.” So, Antonio moved his wife and three sons to the southern end of the Santa Clara Valley — Morgan Hill — where he became a share cropper, grew oranges and grapes, and made wine. It was 1912.

By the 1920s, with prohibition in full swing, Antonio was living his dream (right). According to the story passed down to me, people came from miles around to buy his high-priced oranges, but he gave the wine away for free. By 1925, his youngest son, Umberto (Albert, who would become my father) was fifteen.

So, Antonio — all four-foot-ten of him — had gotten himself to California. Curiously, though, Antonio did not fit the pattern of the historic wave of Italian immigration he had joined. Many came to America to escape poor economic conditions in the south but, according to reporting at the time and more recent scholarship, most came as migratory workers, intending to stay only long enough to take advantage of high-wage (for them) city jobs, send money home, and return to Italy wealthier than when they left. In fact, 20-30% of immigrants from Southern Italy during the period 1890-1924 did just that. Most came to America without their families. Many others eventually ended up staying, sent for their families once they had found stable big-city jobs, an made significant contributions to the cultural fabric of American cities. But fewer came here to pursue lives similar to what they left behind.

The Questions

So all of this has stimulated some puzzling questions. Why did Antonio not fit the pattern? Why did he not settle in the city to work as so many others had done? If his goal was to be a farmer and winemaker, why did he end up in a coal mine in West Virginia for three years? Why did he travel to the other side of the North American continent to grow grapes and oranges and make wine, when he had already been doing that in Calabria? What sent him half way around the globe to make a life exactly like the life he left behind? Why? Nobody had answered that question to my satisfaction . . . until my nephew Joe (‘Joe III’ in the comments) did some digging on the Internet and learned something that none of us had heard before. I think it may shine some light on some of the questions: why he came to America early in 1909, how he got here, and why he stayed.

The Disaster

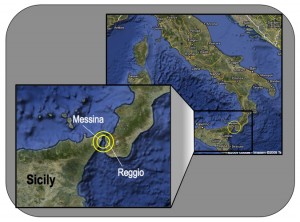

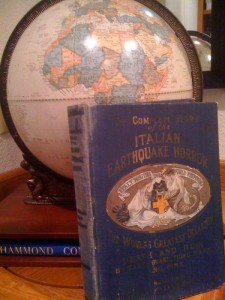

In 1909, J. Martin Miller, published a contemporaneous account of what he called “a disaster more awful and far-reaching than all of Nature’s disasters combined during the century preceding this one.” The cover of his book displayed a long and melodramatic title: The Complete Story of the Italian Earthquake Horror — The World’s Greatest Disaster — Death and Ruin By Earthquake, Tidal Wave, and Fire. His account, still credible after 100 years of analysis, was that more than 200,000 people died in Reggio and Messina, on either side of the Straits of Messina where the earthquake was centered.

Rescuers turned attention to the living, leaving the burial of the dead until the arrival of more help (Miller)

Some Answers

So what does this historic disaster have to do with my questions? Antonio did not seek out the big-city jobs that so many Italian immigrants pursued because be was not qualified — he was an illiterate farmer who couldn’t write his name. So, what future did he think he would have here? He brought his young family, even though he could only get work in a coal mine, because he had no intention of returning home to Italy . . . because there was no home to return to! The entire area around Reggio Calabria was utterly destroyed on December 28, 1908, in the 7.5-magnitude earthquake. The entire region was rubble on both sides of the Straits of Messina. According to Miller’s reporting, thousands of bodies were strewn about unburied for weeks, causing additional thousands to die of disease. All the buildings they had known were flattened. From his point of view, the home he knew no longer existed.![]()

===================================

Epilogue — How Much of This Story Is True?

The details of the earthquake of December 28, 1908, are well documented. Type into Googgle ‘Reggio, Calabria, Messina, earthquake’ and you will find a wealth of detail and the dramatic reactions from around the world at the time, including international rescue efforts much like those taking in place in Haiti today. The contemporaneous Miller book (shown at right), while overly melodramatic in the journalistic style of 1909, is full of details that reflect the reporting from that time and place and dozens of photos that provide some vivid context for understanding the magnitude of this disaster.

The details of the life of Antonio and Maria are accurate in the general outline — not much more is known. However, the feelings and aspirations that drove them — except perhaps for his reaction to the piece of fruit he found in a grocery store in Huntington — can only be surmised. Their generation and their children’s generation in our family are mostly gone, those who remain recall that they never talked much about what happened before ‘the crossing.’ When I was growing up, I heard from my parents that Grandpa “was an orphan.” When asked for details, my aunt Kitty (fourth child of Antonio and Maria, born in West Virginia after my father) told me a summary of what she had heard: “Half the town died,” she said. “All of his family died but him and all of her family died but her. So, they got on a boat and came to America.” When I asked my mother, she said only, “It must have been something like malaria.” Another aunt, Isabel, told me that she thought Antonio had come first and Maria and the two boys came later.

As I’ve researched this story, one problem has been a nagging disappointment. I studied a great resource for families of immigrants — the Ellis Island Foundation website (http://www.ellisisland.org). This terrific service allows you to search passenger lists, and even view the actual hand-written ship manifests, of commercial ships that brought immigrants to the US. We know that Antonio and Maria came to America by ship by 1910 (since their third son, my father, was born in West Virginia in 1910), but I have found no entries on any of the passenger lists of those ships that could have been ‘our’ Antonio, in either 1908, 1909, or 1910. His fairly common first and last name appeared 25 times, but all were the wrong age, came from the wrong parts of Italy, in the wrong years, and with other ‘wrong’ details. The closest match was one Antonio with the right last name who came from Montebello (500 miles to the north) in April of 1909, departed from Naples, was too young to have a nine-year-old son (and too young to have died in 1927 at the age of 56), and identified his marital status as single. Why is ‘our’ Antonio missing from those ships? I’m still working on a hypothesis. Conflicting stories will have to be sorted out. It will have to remain a work in progress for now.

🙂 I hope everyone who is interested in this story will read the ‘Comment’ below from my nephew Joe III. From his own research, he has added significantly to the story; and I appreciate his input tremendously.

Dan, This is good stuff! Thanks! One comment more, tho: Oranges? I thought it was apples.

Bunny

Funny. I’ve heard it both ways. We should take a vote among those who have heard the story and see what wins. What was it: an apple or an orange?

It’s interesting to me how even the outlines of our ancestors lives can resonate and link us to them.

Great story, and the historical background and answer to the mystery of why Antonio and Maria migrated was fascinating, particularly given the recent earthquake in Haiti.

Good job, Dan! I always heard it was apples in the company store — I never heard of oranges until this year from you. Also, I’m pretty sure Al (Umberto) said they grew apricots and prunes (a variety of plums) in Morgan Hill (a la “The Pruneyard”), but I have a feeling that it was lots of kinds of fruit and whatever kind of fruit was at hand on the table to hold up while telling the story might have become part of the story.

Here are a few extra details about the earthquake and tsunami that enrich the story further.

Beyond the recent events in Haiti that make the 1908 earthquake even more horrendous that Haiti plus the Indonesian tsunami combined… The earthquake was at 5:21 AM Monday morning after a Friday Christmas and a weekend of continued partying. It was still dark and almost everyone was still in bed. The buildings, which were built not just along steep hills, but up against and into steep cliffs very close to the ocean, and they collapsed during the first shaking. Many people were crushed instantly in their beds.

Unlike the Indonesian tsunami, which took 40 minutes to arrive and warned slightly by first drawing the ocean out along a shallow beach, the 1908 tsunami came “moments later” — I’ve seen mention of 2 minutes later and 10 minutes later. The first wave was 40 feet high, and washed the rubble of docks, buildings, and bodies out into the ocean within minutes. People who were “only” trapped by collapsed buildings were soon drowned. In Messina, as in Haiti, the prison was severely damaged, but those prisoners who weren’t crushed or otherwise trapped immediately were also not freed from their cells, so they drowned a few minutes later. 90% of Messina’s buildings were totally destroyed, and the 25-50% of Reggio nearest the ocean was totally destroyed — and then washed into the sea within minutes.

There had been a major earthquake about 130 years before, and several somewhat smaller and further away earthquakes in the 5 years before 1908.

As for the possibility of Antonio coming from Naples… Reggio is built between steep cliffs and a deep bay. The docks were totally destroyed. The railroad tracks, telegraph lines, and road from the north were destroyed and other than a few large ships nearby, any aid had to stop miles north on the railroad and be moved manually into Reggio from there. Evacuations were done only by ship, and the evacuees were taken to Naples, the nearest major port, so Antonio and Maria should very likely have come from Naples to America (other candidates are Le Havre and Palermo, but Reggio or Messina are extremely unlikely).

The U.S. ambassador was out of town and his deputy was killed in the earthquake. But the seismograph had been invented 28 years earlier and new seismographs had been installed by the Smithsonian allowing the U.S. to know about the earthquake when it happened, although the triangulation was not very good yet. The first ships to come were from Bulgarian and Russian navies.

Reggio was (and still is) primarily an agricultural town. But it was surrounded by small towns, with many of them closer to the epicenter than Reggio. Entire towns simply crumbled into dust burying their entire populations in their beds. If Antonio and Maria were from a small town, their birth records probably vanished with the entire town.

So, imagine the experience of a survivor living in Reggio — awakened in your bed up on the cliffs above the town after a 3-day Christmas weekend, half the town collapses during the 40-second tremor, then as you are looking down from the cliffs, a 40 foot wave comes in within minutes bringing the boats of the harbor inland. Then the wave goes back out, washing the rubble and bodies out to sea, taking all the boats with them. You’re left with sea in front of you, mountains behind you, there is no communication into or out of the city by boat, rail, road, or telegraph. One quarter of the people you know have vanished (half in Messina) and another quarter die of diseases in the next three months. If you’re lucky, you get evacuated to a town 500 miles north where the speak Neapolitan rather than Sicilian (which is a significantly different language, not just a dialect). Amazing! one might think God had something against your town and fellow citizens!

Dear Joe III, I am thrilled that you added so much vivid detail to the story of our ancestors (your great-grandparents). You have done significantly more research than I have and your enthusiasm and encouragement have contributed a lot to my enjoyment (and the telling) of our family story. I had hoped you would chime in with the fruits of your research and you did not disappoint!

As I have communicated to your mother, the ‘apples/oranges’ controversy is probably my mixing of two stories: the story in the grocery store (which I am coming around to believe was about an apple) and the ‘oranges and wine’ story from the prohibition era, which was told to me, from two sources, about oranges. You are surely right that a farm in the vicinity of Llagas Creek in Morgan Hill would have also grown prunes and apricots and more — not to mention grapes — as they do today. You are also right about the way my Dad, your grandfather, told a story. We can imagine him reaching in a bowl on the table, grabbing whatever fruit was there, and using it to tell his story.

The ‘company store’ you mentioned is also the way the story was told to me. However, when I visited Red Jacket in 1973, I found it to consist of about 150 yards of gravel road with the (pictured) mine shaft at the end. How did I know it was Red Jacket? There was a round, rusted “Red Jacket Rotary” sign down in a ditch beside the gravel road. It looked like it had been there a long time. Further down the gravel road, there were a few houses (with people idly sitting on front porches), an old, small run-down church-looking building, and what used to be a one-pump gas station. There wasn’t anything else (in 1973) that looked like any kind of store. The next ‘town’ I was able to find that had anything like a store, Huntington, was several miles away. There were several ‘wide spots in the road’ along the two-lane road that was marked ‘Hwy 65’ that may have believed they were towns (as I see today on Google maps), but none with anything that looked vaguely commercial. Huntington looked, on that day, to be a believable place that Italian mine workers may have gone, sixty-plus years before, for their shopping. Aunt Kitty emphasized to me that he went to that store because the shopkeeper spoke Italian, which might not have been the company store. Once again, fading memories and mixed stories leave us with uncertainties. She was, of course, also telling a story that was told to her long after the fact. Thanks again, Joe, for adding so much richness to the story. Dan

I so enjoyed the story and all the comments!

I, too, enjoyed this story and the subsequent comments. It makes me wonder why my father and his family left Winnepeg in the 50s, especially given what we’re now seeing of Canada through the Olympics.