American Independence Day — Brexit Number One???

“It ought to be commemorated,

as the Day of Deliverance

by solemn Acts of Devotion

to God Almighty

. . . solemnized with Pomp

and Parade, with Bells,

Bonfires, and illuminations

from one end of this continent

to the other.”

— John Adams, July 1776

It’s here, America’s national birthday! Flags are flying, there will be fireworks, concerts, and parades all across the land. Our national anthem will be played by bands and sung by soloists at every opportunity, and well it should be! For our red, white, and blue flag and the nation for which it flies has endured through hard and confusing times – beginning at its founding in the turbulent 18th century through to the present hard and confusing times here in the turbulent twenty-first. Congratulations to us all!

These two hundred forty years haven’t been easy. Of course, like most of the major inflection points remembered along the span of our history, this one is remembered with a focus on winning a war – the war for independence from the British Empire. OK, yes, the cleverest among us are welcome to call it The First Brexit, well, the exit from Britain by the British colonies of North America.

As such, the military victory itself was a bit of a surprise. Military buffs may be interested to know the details of the strength of Washington’s American army that defeated the powerful military force of what was arguably the largest empire the world has ever known. What did it take? On May 12, 1776, General Washington reported the Duty Roster of the Continental Army in a dispatch to the Congress as follows:

- Commissioned officers 589

- Non-commissioned officers 722

- Present and fit for duty 6,641

- Sick but present 547

- Sick but absent 352

- On furlough 66

- Absent without leave (AWOL) 1,122

That was the total strength of the American army. Stunning, eh?! How did it happen? Well, lots has been written about the war . . . but . . . the short answer is . . . well:

The French helped us. (Shhhhhhhh. Don’t tell anybody; some are still embarrassed.)

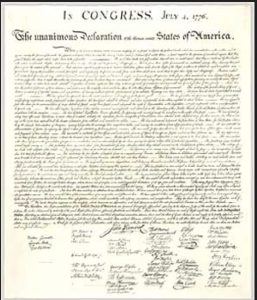

The Declaration

Even though our national anthem doesn’t mention it, we all know, of course, that Independence Day commemorates more than just winning a war. There were powerful ideas at work that made it happen. The ideas that flowed from the pen of Thomas Jefferson are still revered today, across America and in many parts of the world. A declaration published for all the world to see enumerated twenty-eight major grievances against the British King and eloquently proclaimed the necessity “for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.” In the document, the king was defined as a tyrant “. . . unfit to be ruler of a free people.” Finally, after claiming the right “to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do,” the fifty-six signers of the document pledged their fealty to the values they held most dear: “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

The debate in the Second Continental Congress on whether to adopt the declaration was vigorous and required some significant compromises – including what many refer to the ‘Original Sin’ of the American experiment in democracy. In Jefferson’s original draft, he included the following statement among his grievances against the king:

“he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to endure miserable death in their transportation hither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold …”

This clause caused a loud uproar among the southern slaveholders (of which Jefferson was one). To prevent the southern colonies from walking out of the Congress, this clause in Jefferson’s original draft had to be removed. So, the required unanimous vote of the thirteen colonies to separate from England as a new nation required a commitment to slavery. John Adams predicted to Benjamin Franklin (his actual words) “Mark me, Franklin. If we give in on this issue, there will be trouble one hundred years hence. Posterity will never forgive us.” Remarkably, his ‘prediction’ (the Civil War) came true almost ninety years later. Formal recognition of equal rights for the descendants of American slaves wasn’t enshrined in law until a hundred years after that.

And, yes, we’re still working on it.

The Fourth of July

Finally, the solemn celebration of the historic day the Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to approve the declaration formally breaking away from Britain (Brexiting?) has taken place for the past 240 years on July 4. Once again, John Adams predicted how this occasion would be celebrated (again, his own words in a letter to his wife Abigail on July 3 1776):

“I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shows, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

So, did we get it right? Well, almost. Adams was talking about the day the declaration was approved in the Second Continental Congress. The day to be celebrated? July 2nd, 1776.

Adams’ letter to Abigail, July 3, 1776 (the quote is top of page three)

Happy Independence Day!

Click to download a PDF of this article: ConVivio_July4_2016 ![]()

P.S. Why did the date July 4 appear on the declaration as it comes down to us today? While the vote was taken on July 2 (the actual event to be celebrated), July 4 was the date the document was printed, distributed, and read from street corners, churches, and other meeting halls throughout the colonies. An aside — the 56 signatures that appear on the document took several months to be actually penned. Congress made a rule that no one would be allowed to sit in the Congress without affixing their name to the founding document; so, some of those names represent people who were not present on July 2.

Eloquently said! Happy 4th of July to you!

Really Interesting!

Happy 4th to you and Gretta!