To Witness the Miracle

“We are here to witness the miracle.”

— Ray Bradbury

“So, what’s it all about?”

— An American college student in Florence

Since this year, 2020, has not been kind

to travelers (or anyone really); some of us

who have enjoyed the pleasures of travel,

pleasures that have been denied to us

during this COVID year, might want to remind ourselves

of some ideas that emerge from an important question.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Why Travel?

Kappa’a, Kaua’I, Hawaii — A taxi to the BART station, a train to the airport, a series of hurry-up-and-wait movements, and we find ourselves on an airplane, seatbelt buckled, ready to go. Hours later, a smooth landing, more rolling through another airport, a taxi, and a hotel — and here we are! A comfortable place to sit, a glass of wine overlooking the ocean, this was clearly a good idea. No question about it.

We have arrived. Now what? What exactly am I looking at? What should I think about?

— • —

A Clearing

In the 1950s, philosopher Martin Heidegger suggested that, if you can clear away all of the ‘stuff’ that you carry with you that clutters up your life, what emerges from that clearing will help clarify the world around you. He called it (among other things) “truth.” That sounded useful; so, I tried to do that — to make such a clearing — since, here on a beach on an island in the Pacific Ocean, I seemed to be in a place conducive to the making of clearings.

We were sitting at a small patio on the edge of the northern-most Hawaiian island: Kauai. Looking out at that vast ocean, it is easy to let go of things that usually clutter up your mind. The “clearing” that remains offers a lot of room for large ideas to appear, and even a few small ones.

So, what shows up in that clearing?

Surprisingly, the ideas that emerge are not complicated, but simple observations that might be obscured by the details we think about on “normal” days in more familiar places. OK, like what? Well, as I look out to sea, the scene is dominated by one thing: the horizon, just a line, really. I notice that there are no straight lines in this scene, just this one decidedly curved one. No doubt about it, the left and right “ends” of this line that forms the horizon are clearly lower than its midpoint. There can be no question that the complete object, of which this piece of horizon is a part, is not flat.

This observation argues clearly and simply for a round earth. OK, so the earth is round.

That was easy.

Since this “fact” is a relatively new one in human history, I marvel at the power of whatever must have cluttered up the minds of people only five hundred years ago that could have obscured the simple observation that emerges from the clearing I see here. Did nobody notice in all of generations that have walked the earth that the only truly straight lines in existence were man-made? Amazing! And to think that sitting here at the edge of this island made this historic piece of knowledge obvious — a round earth — knowledge that had escaped so many smart people for so long.

Setting aside my amazement for a moment, all the other wonders and beauties we can observe on this island lead eventually to other questions not as easily answered. They are not so much questions about the natural beauty we see around us, but … something else.

OK, so anyone who has tried to ask the “Why?” question knows that it’s never quite that simple. “Why what?” What are you really asking? Why is it round? Why does the water move the way it does? Why does the land occasionally rise above it? The “Why?” questions continue until you stop to consider that there is a question at the root of all of them:

“Why am I here making these observations and asking these questions?”

Of the many humans who have ventured an answer, one writer has held my attention for some time. On the day Neil Armstrong first walked on the moon, science fiction writer Ray Bradbury answered that question for Walter Cronkite: “We are here to witness the miracle,” he said.

–> We are here to witness the miracle. <–

Lots of writers have offered the opposite view that we human beings ARE the miracle — that all of creation has had the primary purpose of bringing human life to this planet. Bradbury’s very different view begs three further questions:

One: If WE are not “the miracle,” then what exactly IS the miracle?

Two: Why does the miracle need a witness?

and, of special interest to artists and writers,

Three: What are the responsibilities of beings created to witness to such a miracle?

While seeking answers to the large questions that emerge from ‘clearings,’ one might ask a smaller one: –> Where does one go to get a closer look at such a miracle?

So, we travel in search of it.

Writers have been telling us that for a long time, and they’ve identified different kinds of miracles. Thornton Wilder has a character who explains that for us in his play Our Town — and she was a character who spent a lifetime without ever leaving Grovers Corners. She observed: “It seems to me that once in your life before you die you ought to go see a country where they don’t talk in English and don’t even want to.” And why is that worth anything? Mark Twain answered this way: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” And he went on to say, “…nothing so liberalizes a man and expands the kindly instincts that nature put in him as travel and contact with many kinds of people. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.” When faced with a contrary argument, Twain got specific in his book of travel stories, Innocents Abroad: “The gentle reader will never, never know what a consummate ass he can become until he goes abroad. I speak now, of course, in the supposition that the gentle reader has not been abroad, and therefore is not already a consummate ass. If the case be otherwise, I beg his pardon and extend to him the cordial hand of fellowship and call him brother.”

Back to “The Clearing”

If travel is a way of making ‘clearings,’ maybe Heidegger’s “truth” is too large a treasure to expect to find in any single clearing. Maybe the grand moments we expect — like standing before Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence or staring up at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome — maybe they are not the most significant of the ‘humanizing’ moments that Twain spoke of. Perhaps more important are the small moments of connection that, when strung together, can add up to ‘truth,’ or some approximation of it. Maybe they can consist of fleeting moments that flash brightly and are then gone. Looking back on our years of travel, some examples emerge.

Humanizing Moments

I recall a weekday night during our first visit to Florence in 2001, we walked around the corner and dropped into a small neighborhood restaurant for dinner – Nello’s. It wasn’t busy, so we struck up a lively conversation with the waiter, who identified himself as “one of the owners.” He answered our touristy questions about Florence and we answered his about San Francisco. We talked about what it was like to live in these two similar places spread so far across the world. He spent a lot of time with us and, near the end of the evening he brought three glassed and we sipped Amarone together for a while before we left. It was delightful. We felt we had made a ‘connection’ with a ‘local’ and it felt good.

When it came time to find a place for dinner on the weekend, we remembered the nice time we had on Tuesday and decided to go back to Nello’s. What the heck, maybe that same guy will be there. That could be fun. So we did.

This time, a Friday night, a tour bus had unloaded and the place was jammed. The same guy was there again, but he was so busy we barely got a glimpse of him. We were lucky to get a table for two in the corner. We greeted him warmly and hoped for a moment of recognition but there was none. Were we ready to order? he asked. I mentioned that Gretta and I had spent the afternoon at Il Academia, which we had talked about with him on Tuesday, but he simply asked, “Some wine?” He took our wine order and left without a nod of recognition. We wondered, had we offended him? What happened to the ‘connection’ we thought we had made? Over the course of the meal, looks passed between us and the waiter indicating that something seemed missing but nothing was said. We decided, he’s just too busy. So, we lingered over dinner and waited until the ‘tourists’ had mostly cleared out. When he noticed that we were still here, he finally came over to us and asked if there would be something more. I tried again to engage him in conversation and commented, “this place is quite different when the tour bus unloads, eh? It was really quiet on Tuesday.” He said, “If you were here on Tuesday, you met my identical twin brother.” He and I looked at each other for a long moment and realized what had been missing. He smiled. “Oh, so we HAVE met. Or so it seemed.”

Yes, another connection.

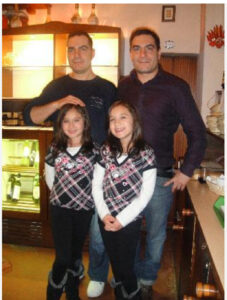

Twin brothers at Nello’s in Florence

Such connections can happen in surprising places. One foggy Spring day, on our last day in London in 2003, we got all dressed up to have “High Tea” at the world-famous Savoy. I wore my best Fedora — a “Sinatra-esque” hat like the one my Father wore when he wanted to look dignified. In the restroom of all places, a distinguished-looking gentleman, dressed in a three-piece suit was standing at attention in his role as the restroom attendant. When he handed me a towel, I asked him with mock gravity, which he seemed to understand, “Tell me, sir, is mine the only Fedora in all of London?”

Yes, sir,” he replied returning my serious expression.

“So, does that mean that all of my efforts to bring Fedoras back into fashion have failed?”

“Yes, sir.”

The momentary grin we exchanged as I tipped my hat to go and dropped a few bills in his jar was worth every bit of the price of afternoon tea at the Savoy.

Finally, on a sunny day in Paris, we were sitting at a shady spot overlooking the Luxembourg Gardens. Gretta was drawing the scene of Parisians enjoying one of their unique spots of civic beauty and I was sitting with my notebook, trying to look like a writer. An older couple walked up and leaned on the stone wall in front of us and we struck up a conversation. They showed an interest in what we were doing — “Gretta paints with watercolors,” I said, stating the obvious.

“And you are a writer?” she asked, pointing at my notebook.

“Oui,” I grinned.

As if in reply, she said, “Let me tell you a story.”

So, sensing an opportunity, I pointed my iPhone and pushed the record button, surreptitiously, I thought. Turns out that they had met as teenagers here in Paris a very long time ago, fell in love, but went the separate ways that life took them — he to the army and she to marriage and children. After many years she returned to Paris — now a widow — and, at the suggestion of her grown son, looked him up on Facebook. And now, here they are, they live in Paris together, where they belong, and were clearly celebrating that fact. As she told her story, the gentleman and I exchanged glances at each other and at my iPhone and he nodded approval. When she was done, I said, “With your permission … “ and I gestured to the iPhone to admit my intrusion. She interrupted me, “Yes, I noticed. It’s a good story, isn’t it? Perhaps you’ll write it down.” We bid each other good day and they were off.

A good story.

The small moments of connection never seem to stop, if you look for them: a woman from the East Bay we met on a boat on Lake Annecy … a bottle of homemade wine gifted to us at the end of a stay at Pomerlo Vecchio in Umbria … an American college student in the Academia in Florence, looking up at Michelangelo’s David, who asked me, “This David is supposed to be a big deal. What’s it all about?”

So, I told him a story that had been told to me — about an inspiring mythical character and a story told in stone by a sculptor more than 500 years ago — “and here we are still looking at it with admiration.” I think he “got it.”

There are many small miracles to witness when clearings are made.

![]()

Hi Dan,

Thank you for the wonderful reflections on travel and connections and so much more.

I miss our travels, as I know you and Gretta do, as they always open up new opportunities and friendships. You made me recollect conections with so many over the years:

o Antonio and Martine who we met on the Algarve and traveled to Portugal with. We connected a few years later in Belguim where Martine’s family lived.

o Linda, Claudia and friends who I met in New Zealand on a cycling trip and spent many years cycling with in the Bay Area. We have lost touch and this reminded me I need to reach out.

o Special travels with local friends, Danny and Barbara, exploring new areas for us and meeting new friends.

Thank you for inspiring the memories Dan.

Thank you for your reflections and thanks for reading.

Thanks, Dan, for a delightful reflection.

Your answer to the question of “What is the miracle?” is ONE, excellent answer. Those moments of connection with a stranger are indeed miracles, as are those surprises that sometimes occur with an acquaintance or co-worker or friend where you find an unexpected moment of existential harmony that moves you to a deeper level with each other.

That’s probably not the answer Bradbury had in mind given the context of the moon landing, but given my recollections of his writings I feel confident that he would have agreed that it is a good answer.

The movie “Soul,” which came out recently, besides being a wonderful celebration of music, especially jazz, also has something to say about your question. In that movie, the question revolves around what is your “spark;” but the wordless answer at the end of the film relates, I think, directly to your question. I will say no more, lest I spoil the film for you. I highly recommend it.

Earlier in the film, there is a discussion of how there are times in playing music that you can become so thoroughly one (my words) with the music that you enter into a different dimension (again, my words — I do not recall the exact way it is described in the movie). There are times when I have had that experience as I was playing, particularly improvisationally — an experience of connecting to something beyond the piano, beyond the room I am in, beyond the life I am living. Your word “connection” may still be the right word, but here it is a different kind of connection, and I think it is another example of the “miracle.” And it is portrayed very thoughtfully in the film. (Here, I should pause to say thank you, Dan, for inspiring me to learn the piano, which allowed me to experience such a miracle.)

But Bradbury said we are here to “witness” the miracle. One might ask: But aren’t you creating, rather than witnessing, the miracle in those musical moments? I would answer: Not entirely. Even though I have had a hand in the creation of the music, in those special moments it feels like the music is in charge and I am just along for the ride — witnessing the miracle of the music even though it may be flowing through my own fingers.

In conclusion, the miracles are many. And in all their forms, what a great gift they are!

Thanks for opening a door for me to make a new connection to Bradbury. The work of the writer in connecting us to people we have never met and helping us to see things we have never seen is, too, a “miracle.” They are everywhere, if we can only see.

Tom Faletti