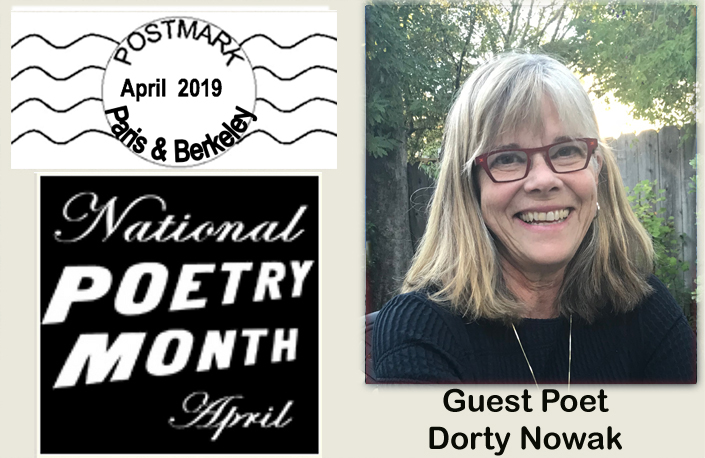

National Poetry Month Is Here — April 2019

Dorty Nowak is a writer and artist living in Paris and Berkeley who writes frequently about the challenges and delights of multi-cultural living. Among life-long achievements, she helped found the Oakland School for the Arts and contributes to artistic projects on two continents. Dorty was ConVivio’s first ‘Guest Poet’ (has it really been) nine years ago.

We welcome her back as today’s ‘Guest Poet.’

— Click below to download a PDF of this post:

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

ConVivio Again Presents “Guest Poets” for National Poetry Month

In celebration of National Poetry Month, Dorty Nowak returns to ConVivio and offers the following poems by “two of the greatest in the English language.” She observes that “old age and death have long been fertile subjects for poets, among them T.S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas.” In that category, she offers Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Dylan Thomas. And, as she has said before, “because I’ll never pass up a chance for extra credit” she gives us one of her own creations.

From Dorty Nowak

Dorty introduces Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” with a story: “Recently I listened to a recorded talk Eliot gave in 1950 in which he said “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” embarrassed him. Since that remarkable monologue helped catapult him, at age twenty-six, to fame, I was surprised. Eliot didn’t elaborate on his embarrassment, leaving me to assume it was because he considered himself not yet a master of his craft. However, poetics aside, Eliot created in ‘Prufrock’ a narrator poignantly and perceptively meditating on the limitations of age. For a young poet to have accomplished that is nothing to be embarrassed about.”

The

Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

by T.S. Eliot

S’io credesse che mia risposta fosse

A persona che mai tornasse al mondo,

Questa fiamma staria senza piu scosse.

Ma percioche giammai di questo fondo

Non torno vivo alcun, s’i’odo il vero,

Senza tema d’infamia ti rispondo.

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question …

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair —

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin —

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume?

And I have known the eyes already, known them all—

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

And I have known the arms already, known them all—

Arms that are braceleted and white and bare

(But in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!)

Is it perfume from a dress

That makes me so digress?

Arms that lie along a table, or wrap about a shawl.

And should I then presume?

And how should I begin?

Shall I say, I have gone at dusk through narrow streets

And watched the smoke that rises from the pipes

Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows? …

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully!

Smoothed by long fingers,

Asleep … tired … or it malingers,

Stretched on the floor, here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet — and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all;

That is not it at all.”

And would it have been worth it, after all,

Would it have been worth while,

After the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets,

After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor—

And this, and so much more?—

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all.”

That is not what I meant, at all.”

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use,

Politic, cautious, and meticulous;

Full of high sentence, but a bit obtuse;

At times, indeed, almost ridiculous—

Almost, at times, the Fool.

I grow old … I grow old …

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?

I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves

Combing the white hair of the waves blown back

When the wind blows the water white and black.

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

— T.S. Eliot, 1915

————————————————————————–

Dorty notes that “Dylan Thomas’ celebrated poem “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” is very different in tone. Written a few years before his death at age thirty-nine, the poem is an exhortation specifically to his father, but generally to mankind, not to give in to the accumulated disappointments and frailties of age. Unlike “Prufrock” Thomas’ poem doesn’t dwell on specifics to make its case but rather relies on the raw power of emotion magnified by phrase repetition.”

Do

Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

by Dylan Thomas, published 1951

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

——————————————————————–

Again, from Dorty — “A few years ago, I wrote ‘Coda’ as a tribute to my grandmother. It’s a poem I couldn’t have written as a young person. Now a grandmother myself, I understand what my grandmother taught me, by example, about courage and resilience.”

Coda

By Dorty Nowak, (published by Drunk Monkeys in 2017)

Too big for your body, the whale of a bed will go on sale; also the dresser, its

three-linked mirrors tall as sails.

I empty drawers of froth-edged linens sent from Sligo, clippings from concerts that spoke of early promise, a few hairpins. Find, beneath a crush of scarves, a silk sack, striped silver and gold. Inside,

a prosthetic breast.

Flayed by a country doctor when I was thirty-three.

I cradle its weight in my hand. You ask to keep it, a bit of ballast.

In the last drawer, two boxes of dime store jewels, gifts from music students. I run beads smooth as seaweed through my fingers, dangle jeweled earrings. Their cast-off colors dance on the surface of the pale green spread. You know the name of each child. The boxes, and their names, go with you.

Only the piano is left, shipped from Austria, a gift from your father when you were six. Grand vessel you commanded through two wars, both a brother and husband disabled young. Sorrows you never spoke flowed from your fingers.

Nana, what shall I do with the piano?

Play it.

National Poetry Month Continues

Many thanks to Dorty Nowak for accepting my invitation to serve as ‘Guest Poet’ on ConVivio, once again. You can see Dorty’s previous appearance as a ‘Guest Poet’ on ConVivio at:

——-> Since ‘National Poetry Month’ is . . . well . . . a month long, next week we will be privileged to have an offering from another of our previous ‘Guest Poets’ — Lauren de Vore. Look for that. Others are in the works — we’ll have to wait and see what appears! Dorty and Lauren and I hope that others (YES, YOU!) will take advantage of the opportunity to contribute some of your favorites— either poems written by others or their own creations.

Go For It! There’s a whole month left of National Poetry Month! What are you waiting for?